George Washington’s First Presidential Residence at the Franklin House, Cherry Street, New York, unidentified artist, drawn before 1856 showing house 1770-1780 before remodeling and Washington’s 1789 residency, New York Historical Society

THE FORMIDABLE BOWNE FRANKLIN WOMEN:

MARIA (BOWNE) FRANKLIN OSGOOD, THE FURNISHING OF THE FIRST PRESIDENTIAL MANSION, AND THE NEW YORK FEMALE ASSOCIATION

By Ellen M. Spindler, Bowne House Collection volunteer, with research assistance by Kate Lynch

This article is about a constellation of remarkable Quaker women who lived from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century, all ancestors of the Bowne family either directly or through marriage. They devoted a tremendous amount of effort to charitable work, running the gamut of helping to furnish the first Presidential mansion to establishing free charity schools to educate girls without religious affiliation from families with limited means. For one, Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood, the sumptuous family mansion which she helped to furnish as the first Presidential residence in U.S. history for George Washington has now disappeared except for a commemorative plaque by the Brooklyn Bridge. For another, the independent single Caroline Bowne, Mayor Walter Bowne’s granddaughter, her “Bowne” house remains on West 71st Street in Manhattan. We explore their lives and how their small circle of wealthy Quakers mostly involved in the shipping and printing businesses, as well as politics and civic organizations, intersected both in Manhattan and in Queens.

Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood and the Furnishing of the First Presidential Mansion for George Washington

Mary (Maria) Bowne (John and Hannah (Feake) Bowne’s great-great-granddaughter) was born at Rocky Hill, Flushing in 1754 to Daniel Bowne and Sarah Stringham. In 1774 when she was twenty-one, Maria married in Flushing Walter Franklin (1727-1780), the oldest child of parents Thomas Franklin and Mary Pearsall from Westchester. [1] Noticeably, there was a significant age difference of twenty-seven years between the two. Maria grew up not far from the historic house her Quaker ancestors had built circa 1661 on Bowne Street in Flushing, Queens (“the Bowne House”).

A Miniature Portrait of Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood, American School, 1789 [2]

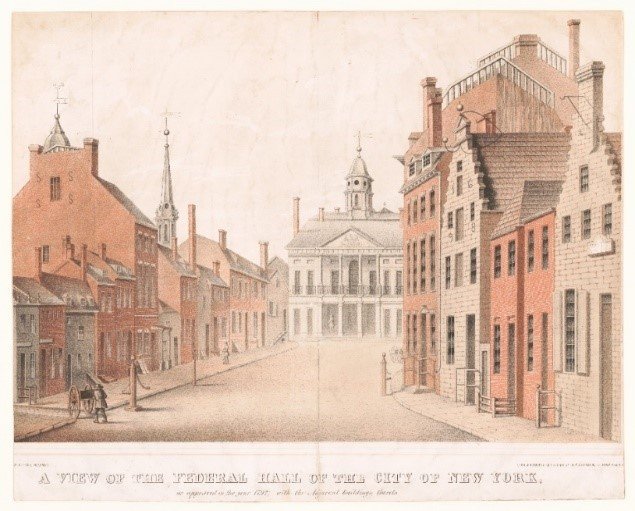

Walter Franklin was wealthy and had inherited a large fortune from his parents that he put into trade and ships. He was senior partner of Franklin, Robinson & Co which had ships bringing goods from China and the South Seas. He built his large Georgian house in 1770 before his marriage on two lots later numbered 1-3 Cherry Street in Manhattan on the northeast corner of Cherry and Queen Street (later known as Pearl Street, and then Franklin Square). [3] The house, known as the Franklin House, had an extensive garden attached and the area was considered by some to be the center of New York aristocracy at the time. [4]

Walter courted Maria from a country house he had previously bought in Maspeth, Queens in 1755. The story told by his great-niece is that he accidentally met a pretty milkmaid on Long Island while driving his buggy there. He drove to the home of her father Daniel Bowne and Maria came in to make tea. After three visits he proposed. [5]

During the Revolutionary War, the Franklin country house is claimed to have been used as one of the locations for the British to plan and launch their invasion of Manhattan in 1776. After Walter Franklin’s death in 1780, the mansion was taken over by his sister Sarah and Colonel Isaac Corsa. Later after Corsa’s death, the property passed to Maria and Walter Franklin’s daughter Maria and son-in-law, Dewitt Clinton. [7]

Walter Franklin was prominent in both political and civic affairs before and during the Revolutionary War. For example, in May 1775, he served on the Committee of One Hundred, and on the First Provincial Congress of the Province of New-York. Walter has been reported by descendants as having retired early with an immense fortune, lived well, and drove an elegant chariot. [8]

Maria’s second marriage was in 1786 to Hon. Samuel Osgood (1747-1813), a Presbyterian who served as a Colonel during the Revolutionary War. Afterwards, Osgood held many public offices including serving in the Continental Congress, State legislature, and as Commissioner of the U.S. Treasury. In 1789 President Washington appointed Osgood as first Postmaster General of the United States. He went on to be the First President of the City Bank of New York (now Citigroup). [9]

A Miniature Portrait of Samuel Osgood, American School, 1789 [10]

After George Washington was elected by the U.S. Electoral College in January, 1789, the Franklin House was selected to be the first Presidential residence by the First United States Congress. The house was already known to Congress as it had previously been occupied by its President. [11] After Samuel and Maria agreed to the request, she helped to oversee furnishing the house with her cousin, the cabinetmaker Thomas Burling. [12]

Prior to Washington’s arrival in New York on April 23, 1789, one week before the first Presidential inauguration at Federal Hall, Congress leased 3 Cherry Street from Samuel Osgood for a sum of $845 a year (@$22,000 today), and passed a joint resolution directing Osgood to “put the house and the furniture thereof in proper condition for the residence and use of the President of the United States.” Substantial alterations were made, including expansion of the drawing room in order to accommodate Presidential entertaining. Except for the upholsterer’s charges, the greatest sum for furnishings (463 pounds) was paid to Thomas Burling for “Mahogany Furniture.” Congress spent a total of eight thousand dollars (@$200,000 today) to prepare the house. [13]

On April 30, 1789, the day of Washington’s inauguration, Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood’s niece Sarah (daughter of Samuel Franklin, Walter’s brother, who married William T. Robinson, of Franklin’s firm Franklin, Robinson & Co.) wrote a letter to her cousin Kitty Wistar describing the elegance of the furnishings:

Uncle Walter’s house in Cherry Street was taken for him [Washington], and every room furnished in the most elegant manner. Aunt Osgood and Lady Duer had the whole management of it. I went the morning before the General’s arrival to look at it. The best of furniture in every room, and the greatest quantity of plate and china I ever saw; the whole of the first and second stories is papered, and the floors covered with the richest kind of Turkey and Wilton carpets…There is scarcely anything talked of now but General Washington and the Palace. [14]

President Washington and his wife Martha entertained frequently while residing in the Franklin House and Martha had a large staff to assist her. Seven slaves had been brought from Mount Vernon, and Samuel Fraunces, the steward (who formerly owned Fraunces Tavern), oversaw a staff of about 20 (these included indentured servants, other slaves, and some paid domestics). [15]

The Washington Family, Edward Savage (1789-1796), collection of National Gallery of Art (painted from sketches made at the Franklin House in December 1789 and early 1790)

The Osgoods dined with George and Martha Washington at the residence at least twice, on October 1, 1789 and February 18, 1790, according to Washington’s diary notes. [16] The Presidential residency was later moved to a larger house on Broadway less than a year later in February, 1790.

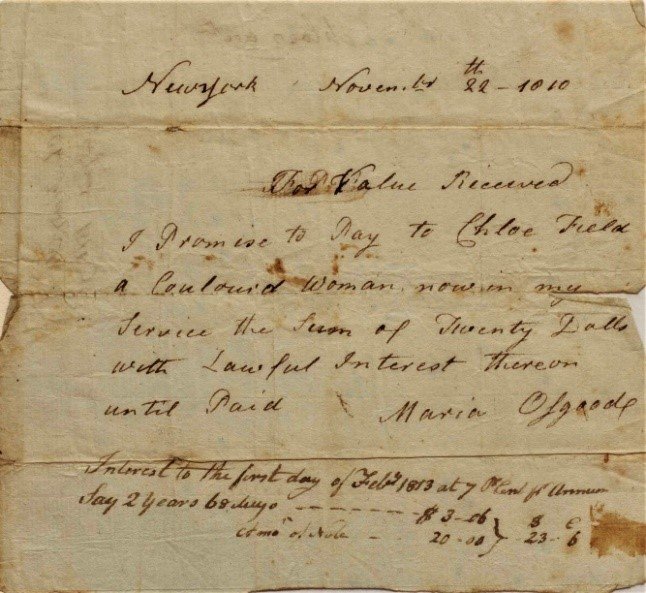

There are only a handful of surviving documentary artifacts relating to Maria during the period after Washington moved out of her home. There are surviving promissory notes from c. 1810-1812, from her about payments owed to a domestic servant Chloe, “a coulourd woman now in my service.” [17] After her death, there was also litigation about whether her conveyance of certain properties such as 11 Cherry Street by deed and will to her children should be honored or instead owed to creditors. [18]

1810 promissory note from Maria Osgood to her servant Chloe Field, Field-Osgood family papers, 1702-1938, Library of Congress [19]

Samuel died in 1813; Maria died the following year in 1814. For a time, her daughter Maria Franklin Clinton and DeWitt Clinton resided in the house on Cherry Street after his mayoral tenure ended in 1815. The mansion remained in the family until 1856 when the heirs of Maria’s daughter Hannah Franklin Clinton (wife of Dewitt Clinton’s brother George) had it demolished and replaced by stores. [20] By the time the Brooklyn Bridge was built and opened on May 24, 1883, only a commemorative plaque near the Manhattan ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge remained. [21]

Text of Commemorative Plaque [22]

Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood’s Cousin Thomas Burling

Thomas Burling (1746-1831) (“Burling”) was an established Quaker cabinet and chair maker, also known as a joiner, who was chosen by George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson to furnish the Franklin House. He received a formal commission from Congress to make Federal-style furniture for the mansion. Thomas’s working years were from 1769-1802 from a shop on Chappel (Chapel, later Beekman) Street, near Franklin Square, and a “Yard” where he sold mahogany, an exotic wood which was a specialty of the family. [23] We believe he received mahogany and other fine wood from the nearby “Burling Slip” located just a few blocks from Beekman Street on the East River at the end of John Street. [24]

Thomas and his wife Susanna Carter had eight children, several of whom went into the cabinetmaking business. Woodworking had been the family business for generations. Susanna’s brother was also a cabinetmaker, joiner, and Windsor chair maker. Burling’s brother-in-law owned six shops along Burling Slip and is believed to have kept a partnership business “Carter and Burling” going during the Revolutionary War. [25]

Although Burling fell away from Quakerism early in his career, he later returned and was known for incorporating simple lines reflective of the simplicity of the Quaker lifestyle into Chippendale and then Federal-style furniture, continuing with a Chippendale style even after 1789. There is a record of a Thomas Joiner donating to the new Quaker Meeting on Pearl Street in 1774 that has been attributed to him. [26]

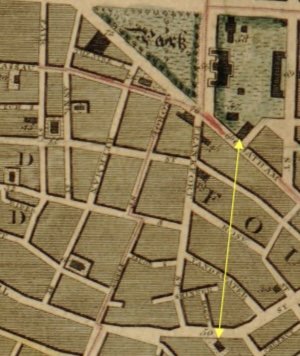

Excerpt of Plan of the City of New York (First Large Scale Plan of New York after the Revolution, circa 1795 (enhanced with arrows) [27]

(showing the intersection of Pearl and Cherry Streets on the upper right corner, the new Pearl Street Quaker Meeting house just north of it, Burling Slip, a Schermerhorne & Bowne Wharf area immediately to its north and another Bowne Wharf five slips to the south of Burling Slip) [28]

Burling was an active member of the New York Manumission Society and had an interest in African-American education, serving as a trustee on the first Board of Trustees of the African Free School in 1786. [29] He would have been a contemporary throughout the post-Revolutionary War period of Robert Bowne (1744-1818), a founding Manumission member and fellow African Free School trustee; [30] and Robert’s brother John Bowne (IV) (1742-1804), who resided in the Bowne House at the time.

Washington and Thomas Jefferson are known to have visited his shop near the Franklin House to select furniture for Washington’s Presidential mansions and Jefferson’s New York residence. A tea table with inlay, card tables, and breakfast and dining tables made by Burling are among the inventory of furnishings for the Franklin Presidential mansion. [31] Burling’s furniture remains at Mount Vernon and Monticello. The Bowne House is fortunate to also have a Burling table in its collection.

The Burling Tripod Stand at the Bowne House

Tripod Stand, Thomas Burling, circa 1769-1783, Bowne House collection

This mahogany round tilt top tripod stand is on display in the 1669 parlor of the Bowne House in Flushing, Queens. As stated by Dean F. Failey, former curator of the Long Island Preservation Society (and former Americana expert at Christies), in his well-known book Long Island Is My Nation, “Were it not for the label of Thomas Burling attached to the underside of the top of this table, one might easily mistake it for a Long Island-made piece. The Bowne family of Flushing owned the stand which was undoubtedly made after 1769 when Burling become a freeman of New York City. Few labelled examples of Burling’s work or the work of other New York cabinetmakers exist.” [32]

Burling label for Bowne House tripod stand, Bowne House collection [33]

According to Margaret Van Cott, Burling’s predilection for Quaker design was shared by most Quaker cabinetmakers. Burling’s tripod stand reflects “a common cultural aesthetic among Quaker cabinetmakers.” [34] The features shared by these stands are a flat top with a rounded edge, disc turning at the base of the baluster stem, a lack of carving on the knees, cabriole legs ending in rounded slipper feet on platform bases, and the use of solid mahogany. Cott advised that three small stands and two tea tables with larger tops are among the nine known objects bearing the label Burling used before the American Revolution. [35]

The label, a small octagon of paper, bears the words, ‘Made and sold /by Thomas Burling/ in Chappel Street, New York’. [36] This label is identical to the one under the small table at the Bowne House. Notably, Chappel (Chapel) Street became Beekman Street only after the Revolutionary War when Burling modified his label to reflect the change. We will never know if Burling knew war was coming when he crafted this stand but certainly the country was soon thereafter transformed.

Maria (Bowne) Franklin’s Three Daughters with Walter Franklin

Maria’s three daughters with her first husband Walter Franklin all lived interesting lives and married important historical persons of the period. Her eldest daughter Maria Franklin (1775-1818), married DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828), later Governor of New York who most notably oversaw the construction of the Erie Canal. Clinton was a well-known public servant serving, inter alia, on the New York City Council of Appointments; as New York State and United States Senators; Mayor of New York City for ten non-consecutive terms commencing in 1803; Presidential candidate for the Federalist Party (1812); and Governor of New York (1817-1822, 1825–1828). [37] He was also on the founding committee of the New York Historical Society and President of the New York Free School Society (FSS), founded in 1805, his entire life. [38]

It is not known if the Clintons ever resided in a house in the West 40’s (now known as Hell’s Kitchen or Clinton), in addition to the country house in Maspeth, Queens eventually inherited from Walter Franklin and Franklin’s sister Sarah. Nevertheless, the family connection came full circle when Samuel Parsons, Jr., the well-known landscape artist, and Bowne descendant, designed the Dewitt Clinton Park opened on 11th Avenue between 52nd and 54th Streets in Manhattan in 1905 in honor of DeWitt Clinton and his Erie Canal project. A garden in Maria’s honor remains to this day in the park. [39]

During their tenure at the Maspeth country house where they resided from 1807- 1828, Clinton used it as a country retreat and made plans to create the Erie Canal, allegedly inspired by the slow, shallow, and navigable creeks adjacent to his property that emptied into the East River. Indeed, it is said in accounts from the time that Clinton was intrigued with the idea of creating a canal from Flushing Bay, Queens to Wallabout Bay in Brooklyn which would bypass the almost-impassable at the time Hell’s Gate at the confluence of the East and Harlem Rivers. [41]

Another daughter Sarah (Sally) (1777-1842), married John Leake Norton who was initially disinherited from an immense fortune by his uncle (and godfather) John G. Leake, including a sumptuous residence called “the Hermitage” on West 43rd Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues and an additional 80 acres, encompassing most of Hell’s Kitchen. Nevertheless, John Leake Norton later ended up inheriting one third of the estate from his mother. [42]

Sarah Franklin Norton, John Wesley Jarvis, circa 1815, private collection [43]

A third daughter Hannah (1780-1855) married George Clinton (1771-1809), Dewitt Clinton’s brother. Her portrait is in the Museum of the City of New York collection. [44]

According to a member descendant of Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood and Sarah Franklin Norton, “The city took it [the estate] eventually by eminent domain. They hired my great-grandfather to track down the genealogical information identifying the family descendant owners. As a clergyman, they assumed he was trustworthy. Earlier, the family had sold a lot of property to J. Astor.”

Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood’s Daughters with Samuel Osgood

Maria also had six children with her second husband Samuel Osgood. Two of her four daughters married prominent citizens of the day. Martha (1787-1853) married the infamous Edmond C. Genet, Minister Plenipotentiary from France to the United States (Citizen Genet). [46] In this role, he had full agency to act on behalf of France’s interests in the new Republic. Genet caused a diplomatic crisis when he began seizing British merchant ships and their cargo, initially with the approval of the newly installed revolutionary government in France in 1789-92, following the overthrow of the monarchy. These and other actions eventually led to his recall, although he continued to reside in this country. [47]

Another daughter Susanna (1795-1834) married Moses Field in 1821 in New York City. Field was considered a notable philanthropist of his day, performing many charitable acts for the poor such as running a soup kitchen, and was the great-grandson of Benjamin Field and Hannah Bowne, John Bowne’s daughter. [48]

Bowne and Franklin Women’s Involvement in the New York Female Association

Around the turn the of 19th century, the Association of Women Friends for the Relief of the Poor, which later became known as the New York “Female Association” (FA), established what became an antecedent to the New York City public schools, operating four Manhattan schools from approximately 1801 until 1845. [49] Caroline Bowne (1779-1848), sister to Walter Bowne who later became Mayor of New York City, and Hannah Bowne (1784-1860), one of Robert Bowne’s daughters, were among the women on the committee appointed by the FA in 1801 to establish its first school and rented a room in that year for that purpose. [50] Originally co-educational but soon admitting only females, the FA schools were open to children of poor parents who did not belong to any “religious society.”

Caroline Bowne was unmarried. Hannah Bowne in 1810 married Benjamin Collins, son of another prominent printer like her father Robert. We know Hannah’s younger sister Jane (Bowne) Haines (c.1792-1843), was also later involved in the FA because of an 1815 sampler made for her by one of the students, Lucy Turpen, at the FA School No. 3 in Manhattan. This sampler is displayed in “Hidden Voices: How Women’s Needlecraft Contributed to the Abolitionist and Free School Movements,” recently published on the Bowne House website. All these women were John and Hannah (Feake) Bowne’s great-great granddaughters.

Other organizational and early members who were Bowne descendants included Catharine (Bowne) Murray (another sister of Walter Bowne, and wife of John Murray, Jr. who was Vice-President of the New York Manumission Society, a trustee of the African Free School, and one of the founders and Vice-President of the FSS); Mary R. Bowne (Mrs. King) (yet another sister of Walter Bowne); Sarah (Bowne) Minturn (another of Robert Bowne’s daughters); Elizabeth Bowne (likely Robert Bowne’s wife); Amy Bowne; and another Hannah Bowne. [51]

Daguerreotype of a miniature of Jane Bowne Haines, courtesy of Wyck Association, date unknown (miniature painted by an unknown artist in New York City in 1835) [52]

Jane and her husband Reuben Haines III wrote three letters in 1812, 1818 and 1829 describing the scale of the number of children taught by the FA charity schools. In the 1812 letter, just ten days before Jane and Reuben’s wedding, Reuben wrote to a friend about waiting on Jane while she attended an examination day with 200 girls in attendance. [53] In 1818 Jane describes attending another examination day where 600 girls were in attendance. [54]

Jane’s marriage to Reuben Haines III took place at the “old” Quaker Meeting House on Liberty Street in Manhattan on May 13, 1812, in contrast to the “new” Quaker Meeting House on Pearl Street right behind the Franklin House where the Franklins, and the other Quaker friends congregated. We know that Samuel Parsons and his wife Mary (Bowne) Parsons (residing at 269 Pearl Street at the time) [55] were invited to Jane and Reuben’s wedding dinner at her father Robert Bowne’s residence at 256 Pearl Street right across the street.

Jane Bowne Haines’s 1812 wedding dress and shoes, Wyck House collection, courtesy of the Wyck Association

Jane Bowne Haines’s 1812 wedding shoes, Wyck House collection, courtesy of the Wyck Association

Jane Bowne ‘s 1812 invitation to Samuel Parsons and his wife Mary (Bowne) Parsons to her wedding dinner at her father Robert Bowne’s residence, Bowne House collection

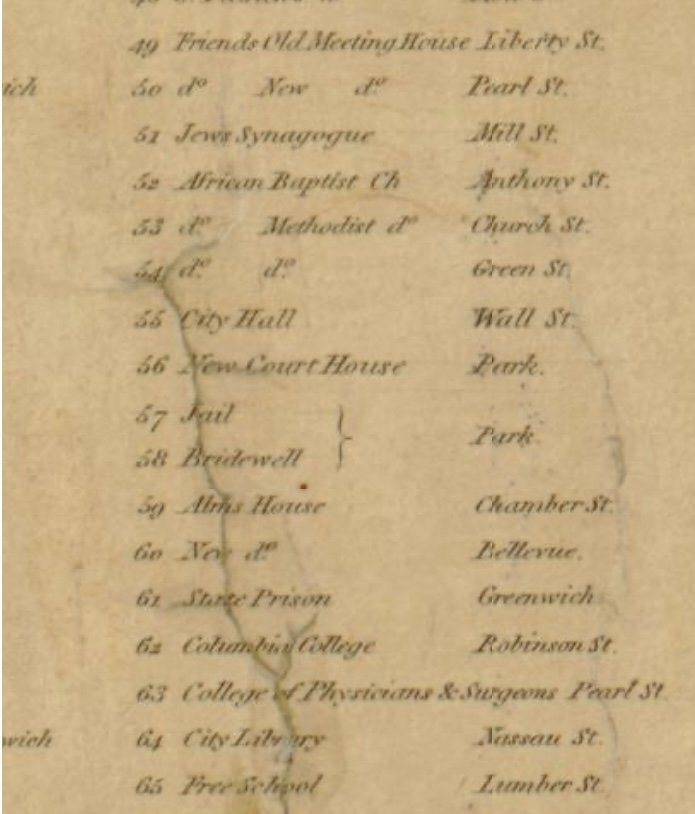

The two 1807 map excerpts below show the Old Meeting House on Liberty Street (49) where Jane and Reuben were married. They also show the first FA charity school on Chatham Street (66) (now Park Row) at the time and the new Pearl Street Meeting house built circa 1775-6 (50). If enlarged via the link provided, one can also see Burling Slip, a free school on Henry Street (67) which would soon become the second FA charity school, and a third on Lumber Street (65) (now Trinity Place) (believed to be a separate religious free school).

The free school at Chatham Street and Tyron Row was the first one built in 1809 by the FSS, formed in 1805 with the involvement of Dewitt Clinton, Robert Bowne, and others. [56] The FSS school initially taught boys and girls, but also gave a room on the lower floor to the FA for their girls’ school. Later, it allowed the FA to teach their girls as well. The Henry Street school was the second FSS school built in 1811. The FSS also gave the FA a room here and the FA school opened in 1812. [57] As of 1814, the FA was reported to be operating these two schools giving elementary instruction and teaching needlework to 300 students. [58] A third school opened in January, 1815. [59] By 1823, it was reported that the FA carried on several schools, with total attendance about 750. [60]

Old Liberty Street Meeting House (left, lower right corner)

Chatham Street free school and new Pearl Street Meeting House (right)

1807 Map Numerical Index

1807 Map Numerical Index

We know Maria Franklin, Maria (Bowne) Franklin Osgood’s great-niece by marriage, was also a member of the FA because an 1815 sampler was made for her by a student Ann Hayden at the Female Association School No. 2. Maria was a daughter of a prominent New Yorker Thomas Franklin, partner in the mercantile firm of Newbold and Franklin and trustee of the FSS, who was the nephew of Walter Franklin. [62]

Ann Heyden for Maria Franklin, Female Association School No.2, 1815, [63]

Another rare FA sampler we are aware of made in 1813 (not previously discussed in our Hidden Voices article) was stitched by Mary McMannus for Mary (Wright) Thompson as a gift to Elizabeth Thompson. [64] Mary Thompson was an active and early FA member who was married to Francis Thompson, a rich Quaker ship owner. [65] According to M. Finkel & Daughter, well-known sampler dealers in Philadelphia, there are only eleven of these small, very finely stitched, samplers from these Quaker charity schools. [66] They were often given as gifts to the Quaker women who were the schools’ benefactors before public funds were received.

Eliza McMannus, for Mary Thompson, a member of the Female Association, 1813, Photo credit: M. Finkel & Daughter

Significantly John Bowne (IV), who resided in the Bowne House at the time, had four daughters, Mary (Bowne) Parsons (& husband Samuel), Ann, Eliza, and Catharine. They were also John and Hannah (Feake) Bowne’s great-great-granddaughters and were all members of the Flushing Female Association (FFA) which ran a subsequent charity school for girls and African-Americans in Flushing established in 1814. [67] They seem to have been inspired by their cousins, Robert Bowne’s daughters and Walter Bowne’s sisters, involved in the earlier established FA schools in Manhattan described above. Walter Bowne was a donor to the FFA before he became Mayor (and perhaps the FA as well since we know his sisters Caroline, Catharine, and Mary were among the founding members).

Another female Bowne descendant of interest, although she is not known to have been a member of the Female Association, is Walter Bowne’s granddaughter Caroline Bowne (1838-1905). Caroline was unmarried and the daughter of Walter Bowne, Jr., and his wife Eliza. She was a single independent socialite and lived in her own “Bowne House” on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. [68]

All these Quaker women defy the stereotype of modest retiring women serving in a limited domestic role more commonly expected in their time, following a path set out by John Bowne’s first wife, Hannah (Feake) Bowne (1637-1678), one of the first female Quaker ministers in the colonies, Britain, and Europe. Even their cousins in Queens were more sophisticated than one might expect and certainly as committed to social reform and civic contribution.

Conclusion

The Bowne Franklin women and their cousins and relations by marriage were a tightly knit constellation of remarkable Quaker women who lived in the mid-18th century to mid-19th century and who intersected socially and philanthropically both in Manhattan and in Queens. All were ancestors of the Bowne family either directly or through marriage. They devoted a tremendous amount of effort to charitable work, including helping to furnish the first Presidential mansion, and establishing charity schools to educate girls from families with limited means. They also married and assisted some of the leading men undertaking civic duties of the post-Revolutionary War period, continuing through the French Revolution and the War of 1812, helping to chart the uncertain path of the new Republic. The Burling table at the Bowne House symbolizes the history of this whole era.

ENDNOTES & REFERENCES

[1] Wilson, Edith, editor, Bowne Family of Flushing, Long Island (New York: Bowne & Co., Inc., 1987), 16 and 25-6.

[2] Displayed for educational purposes only, http://www.artnet.com/artists/american-school-18/miniature-of-samuel-osgood-miniature-of-mari-aa-7snZY9oUY3SQ_E1OroQ_ug2.

[3] Borchert-Cadou, Carol, “Presidential Residency in New York,” https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/presidential-residency-in-new-york/ (Accessed January 23, 2023); Miller, Tom, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House-1-3 Cherry Street,” Daytonian in Manhattan, August 10, 2020, http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2020/08/the-lost-1770-walter-franklin-house-1-3.html. The intersection was named Franklin Square in March, 1817 as an honorific to Benjamin Franklin rather than Walter. Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, Vol. 9. By Common Council (New York: 1917), 64,

https://books.google.com/books/about/Minutes_of_the_Common_Council_of_the_Cit.html?id=qZ06AAAAcAAJ.

[4] Miller, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House” The adjacent Pearl Street later became known as a street of newspaper publishers including as of 1796, the office at 189 Pearl Street of Quaker Isaac Collins, a well-known printer of colonial newspapers and the continental currency who was the father-in law of Hannah (Bowne) Collins, daughter of Robert Bowne who founded Bowne Printing Co., Inc. in 1775 in downtown Manhattan. Harper & Brothers which published Harper’s New Monthly Magazine also later came to be located there.

[5] Wilson, Bowne Family of Flushing, Appendix III, “The Franklin and Osgood Families”, 107-108; “The Franklin family, Sarah Robinson,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record. Devoted to American Genealogy and Biography (1790-1910), Vol. 23, Issue 3, New York, July 1892, 127, https://www.proquest.com/openview/7147de0f147ef3e850373df19421bd6f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=46423.

[6] Graziano, Paul, “History of the Dewitt Clinton House,” The Juniper Berry, Juniper Civic Association, March 6, 2020, https://junipercivic.com/juniper-berry/article/history-of-the-dewitt-clinton-house.

[7] Graziano, “History of the Dewitt Clinton House.” Following Walter’s death, lawsuits were filed with respect to the settlement of Walter’s estate involving virtually all members of the Franklin and Osgood families. Franklin v. Osgood, 14 Johns. 527 (1817), New York Court of Errors, https://cite.case.law/johns/14/527/ ; Osgood v, Franklin, 2 Johns. Chapter 1 (1816), New York Court of Chancery, https://cite.case.law/johns-ch/2/1/.

[8] Wilson, Bowne Family of Flushing, Appendix III, “The Franklin and Osgood Families,” 107 (recounted by Mary Robinson Hunter, Mary Bowne Franklin Osgood’s great-niece).

[9] Miller, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House.”

[10] Displayed for educational purposes only, http://www.artnet.com/artists/american-school-18/miniature-of-samuel-osgood-miniature-of-mari-aa-7snZY9oUY3SQ_E1OroQ_ug2. Osgood appears in John Turnbull’s famous portrait of Washington resigning his commission at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1793, located in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/general-george-washington-resigning-his-commission.

[11] “[Diary entry: 1 October 1789],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-05-02-0005-0002-0001 [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 5, 1 July 1786 – 31 December 1789, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 448–451.] See also “From George Washington to James Madison, 30 March, 1789,” Founders On-Line, National Archives, https://founders.archives.govq=samuel%20osgood&s=1511311113&r=164.

[12] Borchert-Cadou, “Presidential Residency in New York”; Miller, “The Lost 1770 Franklin House.” See generally Wilson, Bowne Family of Flushing. Burling was a descendant of the famous abolitionist William Burling, an early anti-slavery advocate in Flushing. See Thompson-Stahr, Jane, The Burling Books: Ancestors and Descendants of Edward and Grace Burling, Quakers, 1600-2001 (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, Ltd., 2001), 259-280, https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Burling_Books.html?id=l_WMvEcaVBkC; Thomas Burling WikiTree, https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Burling-278.

[13] Borchert-Cadou, “Presidential Residency in New York”; Miller, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House”; Thompson-Stahr, Jane, The Burling Books, 259-280.

[14] In the Words of Women, (Jenet), Archives for the Robinson, Sarah Franklin category, July 22, 2013, http://inthewordsofwomen.com/?cat=240; Wilson, Bowne Family of Flushing, Appendix III, “The Franklin and Osgood Families,” 112. Kitty was the daughter of Mary Franklin (Walter Franklin’s sister) who married Caspar Wistar. The Wistars were the family which originally owned Wyck House in Germantown, Pennsylvania outside Philadelphia where one of Robert Bowne’s daughters Jane (Bowne) Haines later resided after she married Ruben Haines III.

[15] Miller, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House.”

[16] “[Diary entry: 1 October 1789],” Founders Online, National Archives, pp. 448–451.; “[Diary entry: 18 February 1790],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-06-02-0001-0002-0018 [Original source: The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 6, 1 January 1790 – 13 December 1799, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979, pp. 35–36.]

[17] Field-Osgood Papers, 1702-1938, Library of Congress, Box 6, Osgood, Maria, to Chloe Field, 1810-1812, https://findingaids.loc.gov/db/search/xq/searchMferDsc04.xq?_id=loc.mss.eadmss.ms007044&_ start=76&_lines=125&_q=maria%20osgood&_displayTerm=maria%20osgood&_raw_mfer_q=Maria%20Osgood.

[18] Jackson ex dem. E.C. Genet and others v. Wood, 3 Wend. 27 (1829), New York Supreme Court of Judicature, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, and in the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors of the State of New York, Vol. 3, [1828-1841], https://books.google.com/books/about/Reports_of_Cases_Argued_and_Determined_i.html?id=VtYzAQAAMAAJ.

[19] Retrieved by Kate Lynch from the Field-Osgood Papers at Library of Congress, Box 6, Osgood, Maria, to Chloe Field, 1810-1812.

[20] Miller, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House.”

[21] Miller, Tom, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House.”

[22] Miller, Tom, “The Lost 1770 Walter Franklin House.”

[23] Cott, Margaret Van, “Thomas Burling of New York City, Exponent of the New Republic Style,” The Furniture History Society, Vol. 37, 2001, 32-50, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23409213.

[24] Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City,” 32-50. Burling Slip has variously been described as named after a Burling ancestor or Thomas’s son Samuel who took over the business after Thomas retired. In 1791, Thomas had announced that his shop would henceforth be known as Thomas Burling & Son. According to Cott, Burling Slip was named for Samuel Burling, Thomas Burling’s son, according to a family will; compare with Thompson-Stahr, The Burling Books, 79-80.

[25] During the Revolution, the Burling family left to stay in Orange County and in fact received a certificate in good standing from the New York Meeting to the Nine Partners Monthly Meeting. Thompson-Stahr, The Burling Books, 259-280.

[26] Thompson-Stahr, The Burling Books, 259-280. Walter Franklin, George Bowne, and Margaret Bowne are also listed as large donors among a list of 77 donors, with Walter and George each giving at least 150 pounds, 135. See also Meeting House pledge sheet, N.Y., April 29, 1774, Quaker Collection, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pa..

[27] Retrieved by Kate Lynch from the Barry Ruderman Map Collection, Stanford Libraries, https://exhibits.stanford.edu/ruderman/catalog/fn954dp8402, (Accessed January 23, 2023). See also AKRF, Inc preparer, “Archaeological Discovery at Burling Slip,” New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, Burling Slip, NYC Archaeological Repository, https://www.nycgovparks.org/park-features/imagination-playground/archaeologyhttps://www.nycgovparks.org/park-features/imaginat; http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/arch_reports/1341.pdf (Accessed February 21, 2023).

[28] The Schermerhorn & Bowne Slip just to the north of Burling Slip involved property owned by George Bowne as of 1804, believed to be Robert Bowne’s cousin. AKRF, Inc preparer, Archaeological Discovery at Burling Slip, 36, figure 37.

[29] Bretton, Arthur J., A Guide to the Manuscript Collection, New York Historical Society, (Westport, Con: Greenwood Press, 1972), 191; “New York Manumission Society Records 1785-1849,” New York Heritage digital collections, mentioning Burling, Samuel Bowne, John Murray, Jr. (married to Catharine Bowne), among other members, https://nyheritage.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15052coll5/id/30572/; Thompson-Stahr, The Burling Books, 259-280.

[30] On 25 January 1785, a group of nineteen men met at Simmons Tavern for the purpose of “forming a Society for the promoting the Manumission of Slaves; and protecting such of them that have been or may be Liberated.” Among those nineteen were Robert Bowne, John Murray Sr. and Jr., Thomas Bowne, and Samuel Franklin. “John Jay, Anti-Slavery, and the New York Manumission Society: Editorial Note,” Founders On-Line, National Archives, fn. 2, citing John Cox Jr., Quakers, in the City of New York, 1657–1930 (New York, 1930), 62, [Original source: The Selected Papers of John Jay, vol. 4, 1785–1788, ed. Elizabeth M. Nuxoll. Charlottesville]: University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 24–29.], https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-04-02-0013.

[31] Borchert-Cadou, Carol, “Presidential Residency in New York,” 71, Appendix, Inventory of “Articles Furnished.”

[32] Failey, Dean, F., Long Island is my Nation, The Decorative Arts & Craftsmen 1640-1830. (Setauket, Long Island: Society for the Preservation of Long Island Antiquities, 1998), 2d ed. 92.

[33] Failey, Long Island is my Nation, 92.

[34] Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City,” 32.

[35] Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City,” 32, fn.9. In this footnote Cott cites Dean Failey’s reference to the table with a Burling label at the Bowne House and includes it among the three known labelled stands.

[36] Cott, “Thomas Burling of New York City,” 32-50.

[37] Clinton’s New York City Mayoral terms were from 1803–1807, 1808–1810, and 1811–1815). Eisenstadt, Peter R., The Encyclopedia of New York State (Syracuse, New York, Syracuse University Press, 2005), 348-349; “DeWitt Clinton,” Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/de-witt-clinton-park/history.

[38] An account of the Free-School Society of New York (New-York: Collins and Co., 1814), 6, 22, 69, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044096982194&view=1up&seq=11, “Meet Mayor DeWitt Clinton, the man who built New York City’s future,” https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2021/06/podcast-dewitt-clinton-and-erie-canal.html, Bowery Boys, June 22, 2021 (Accessed February 12, 2023).

[39] “DeWitt Clinton,” Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation.

[40] Eisenstadt, The Encyclopedia of New York State, 348-349; “DeWitt Clinton,” Official Website of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/de-witt-clinton-park/photos.

[41] Graziano, “History of the Dewitt Clinton House.”

[42] Miller, Tom, “The Lost Hermitage W. 43 rd Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues,” The Daytonian in Manhattan, December 20, 2021, http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2021/12/the-lost-hermitage-43rd-street-between.html.

[43] A portrait of Sarah Franklin Norton by John Wesley Jarvis is also owned by the Munson-Williams-Procter Arts Institute and is recorded in the Catalog of American Portraits, a research archive of the National Portrait Gallery, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_66.5.

[44] Portrait of Hannah Franklin Clinton, Museum of the City of New York collection, Philip Parisien, ca. 1805, https://collections.mcny.org/asset-management/2F3XC54V7NU.

[45] Holmes, J. B. (John Bute). Map of the Hermitage Farm and the Norton Estate. [TIFF]. [New York : City Surveyor, 1872]. Retrieved from https://earthworks.stanford.edu/catalog/princeton-1n79h6731. The Museum of the City of New York has created an interesting interactive map entitled “The Greatest Grid, The Master Plan of Manhattan 1811-Now” based on a fusion of 92 Randel Farm Maps from 1818-1820, https://thegreatestgrid.mcny.org/randel-composite-map. John L. Norton’s ten lots, from W. 40th to W. 46th Streets can be seen here with Astor property adjacent to the north and George Bowne’s son Robert L. Bowne’s three lots on the Upper West Side and Thomas Burling’s two lots in the Village.

[46] Warren, Elliott, “Edmond Charles Genet,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Washington Library, Center for Digital History, Digital Encyclopedia, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/edmond-charles-genet/ (Accessed January 20, 2023).

[47] Warren, “Edmond Charles Genet.”

[48] Wilson, Bowne Family of Flushing, Appendix III, “The Franklin and Osgood Families,” 107-108; Field, Osgood, The Fields of Sowerby near Halifax, England and Flushing New York, With Some Notices of the Families of Underhill, Bowne, Burling, Hazard, and Osgood (London: Printed For Private Circulation Only 1895).

[49] The organization is described as initially excluding in its rules all members of the Society of Friends and not allowing assistance to Quakers. However, women like Catharine (Bowne) Murray were involved from virtually the outset so the exclusion of Quaker women must have soon changed. Bourne, William Oland, History of the Public-School Society of the City of New York: With Portraits of the Presidents of the Society (New York, W. Wood & Co. 1870), Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/09015801/, 653-4; See also McCarthy, Andy, “Class Act: Researching New York City Schools with Local History Collections,” October 20, 2014, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2014/10/20/researching-nyc-schools.

[50] A document found by Kate Lynch in “The Edmund A. Stanley Jr. collection relating to Bowne & Co.” in the New York Public Library, Manuscripts & Archives (Schwarzman Building) relating to the Association of Women Friends for the Relief of the Poor, dated June 8, 1801, states that the organization, “having concluded that a part of their funds should be appropriated to the education of poor children...whose parents belong to no religious society and who ...cannot be admitted to any of the charity schools of the city,” have appointed a committee to open a school.

[51] Bourne, History of the Public-School Society of the City of New York, 654-55.

[52] Special thanks to Cara Caputo, Manager of Interpretation and Public Outreach, Wyck Historic House for her research assistance about Jane Bowne Haines and transcription of correspondence relating to the Female Association for this article.

[53] Reuben Haines III to James Pemberton Parke, May 2, 1812 (from New York), Wyck Association Collection, American Philosophical Society.

[54] Jane Bowne Haines to Reuben Haines III, November 2, 1818 (from New York), Wyck Association Collection, American Philosophical Society. Jane also wrote another letter in 1829 from New York mentioning visits she had made and intended to make to the Association School. Jane Bowne Haines to Ann Haines, November 29, 1829, Wyck Association Collection, American Philosophical Society.

[55] Samuel Parsons (whose father James had married Mary Burling) was married to Mary (Bowne) Parsons in Flushing in 1806. In 1810 they moved to 269 Pearl Street in Manhattan and received an 1811 certificate transferring from the Flushing Meeting to New York where they remained until 1813. Thompson-Stahr, Jane, The Burling Books, 351. Many Quakers lived in the area, likely due in part, to the proximity of the new Pearl Street Meeting house. This Pearl Street Meeting house was demolished in 1824 as the street became more commercial, eventually moving up to Henry Street and then E. 20th near Gramercy Park in 1840. The original “Old” Quaker Meeting House on Liberty Street where Jane (Bowne) Haines was married was constructed in 1696 and sold in 1825. New York City Landmarks Friends Meeting House and Seminary submission, December 9, 1969, no. 4, LP-0241, http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/0241.pdf.

[56] An Account of the Free-School Society of New York, 71, 78. Robert Bowne and John Murray, Jr. were both early subscribers. Donors also included Robert, Elizabeth and Walter Bowne, other younger Bownes, John Murray, Jr. and other younger Murrays.

[57] Bourne, History of the Public-School Society of the City of New York, 654; Palmer, Archie Emerson, M. A., Secretary of the Board of Education (authorized by the Board of Education), The New York Public School: Being a History of Free Education in the City of New York (London: The MacMillan Company, 1905), 11-42.

[58] An Account of the Free-School Society of New York, 18.

[59] Bourne, History of the Public-School Society of the City of New York, 654.

[60] Palmer, The New York Public School, 41-42; Samplings, M. Finkel & Daughter, https://samplings.com/sampler/eliza-mcmannus (Accessed February 12, 2023).

[61] Retrieved by Kate Lynch from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3804n.ct000812/?st=image&r=-0.05,-0.115,1.099,0.52,0.

[62] An Account of the Free School Society in New York.

[63] Ring, Betty, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 (Two Volumes) (New York: A.A. Knopf, 1993), 318.

[64] Samplings, M. Finkel & Daughter, https://samplings.com/sampler/eliza-mcmannus. (Accessed February 12, 2023). Kate Lynch is credited with bringing this sampler to the attention of the Bowne House. Another sampler made by a Mary Wetmore for Sarah Herbert in 1816 entitled “Industry” from School No. 2 has also been researched and catalogued at Finkel & Daughter, http://samplings.com/catalogue/xlv, 5 (Accessed September 12, 2022). They note that Betty Ring also previously had in her collection the sampler made by Ann Heyden for a Maria Franklin at School No. 2 in 1815.

[65] “Walker Packet Owners,” discussing Thomson, Walker & Grimshaw and the Walker Black Ball Line (2005) https://www.quakerwalker.com/articles/walker-packet-owners (Accessed February 12, 2023).

[66] Samplings, M. Finkel & Daughter, https://samplings.com/sampler/eliza-mcmannus.

[67] The FFA was discussed in some length in in “Hidden Voices: How Women’s Needlecraft Contributed to the Abolitionist and Free School Movements,” recently published on the Bowne House website.

[68] Miller, Tom, “Bowne House-No. 274 W. 71st Street”, Daytonian in Manhattan, December 19, 2014, http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-bowne-house-no-274-w-71st-street.html (Accessed January 20, 2023).

[69] Miller, “Bowne House-No. 274 W. 71 st Street.”