Farming and Family Life in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Text & Slideshow By: Emily Vieyra-Haley

Imagine if you woke up one day and found you had been transported back in time to 1661, and you were living in Flushing on a farm with your family. What would your daily life be like? Let us take a look back at history and find out!

By the 1620’s, the New York City area was under rule by Dutch colonists sent from the Dutch West India Company from the Netherlands. The whole area was known as New Netherland and Flushing is the English pronunciation of the original Dutch name, Vlissingen. When John Bowne built his house in 1661, Vlissingen and its surrounding area was a very different place than what we see today. It had more forests that were filled with beautiful plants and fruits, and animals such as bears, deer, wolves, and foxes. There were many people of different backgrounds living together as neighbors.

During the period of Dutch rule, homes were small and built from wood, with thatched roofs. There would be only two rooms and, in the Dutch style, there would be a bedsteden, or a bed box, that was a bed with walls around it, located in the kitchen. These houses caught fire easily, so by 1657 rules were implemented that required roofs to be made of tiles imported from the Netherlands. Gradually, people started building their homes with brick or stone. As more homes were constructed, they developed into a unique Dutch influenced American style. There are other things inherited from the Dutch that we still have today; for instance, cookie comes from koekje, coleslaw comes from kool sla, and cruellers comes from Krullen.

Farming or being a trader were the two most common occupations for people living in Vlissingen. Farming was open to everyone, and the Dutch government invited people of all nationalities to come and farm the land for them. The Dutch were primarily interested in growing wheat, oats, and rye. The land on Long Island was especially fertile, more so than in Manhattan, and the Matinecocks, Canarsie, Rockaways and Merricks, were some of the many Native Americans who had been living there for years, and were already growing bountiful crops in the area. A visiting Englishman named Daniel Denton reported on the Native American’s knowledge and expertise in agriculture and horticulture, writing, “those Plants and Herbs growing there (which time may more discover) many are of opinion, and the Natives do affirm, that there is no disease common to the Countrey, but may be cured without Materials from other Nations” (Denton 10). They introduced maize, or corn, to the Dutch colonists, as well as a special dish called sappaen made of cornmeal with milk or water. Sappaen was quickly adopted into the diet of the Dutch, who otherwise maintained the same diet they had had in Europe.

If you lived on a farm in 1661 Vlissingen, you and your family most likely lived in a small wooden house, with everyone sleeping in one room. The most prized possession would be the spinning wheel, which would have been used by the women of the household to make clothing for the family. Farmers and their families kept track of time by listening to the sounds of church bells, which rang for religious services, court services, and festivals. Early in the morning, the women in the family started the fire and the food preparation for the day, much of which came from the kitchen garden located right outside the house. Young girls would help their mothers, learning as they worked. Women were also responsible for making the butter and for making the three meals of the day, of which the midday meal was the largest. Those meals were simple, usually a stew.

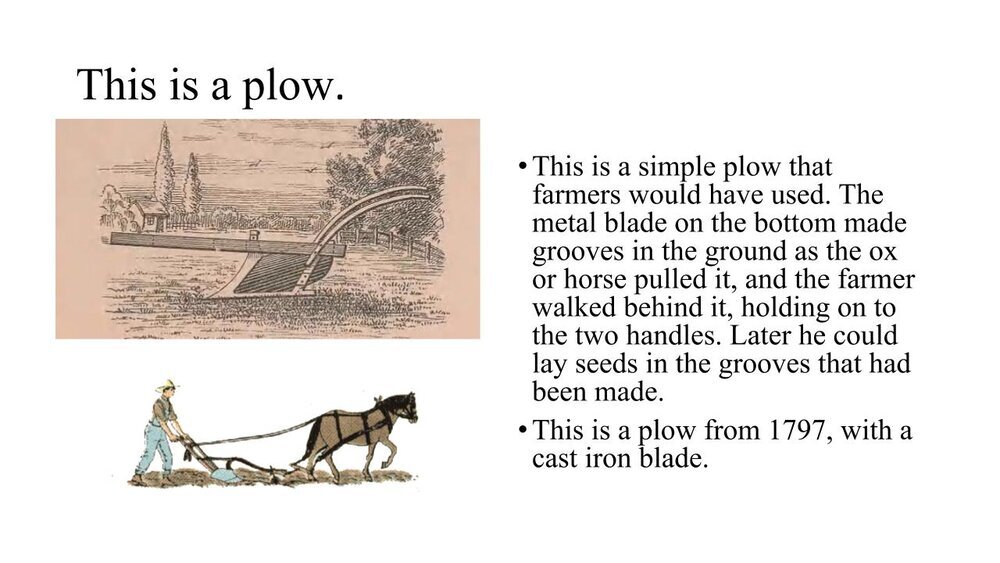

The men were responsible for the heavy labor of farming. They also made their farming tools and the furniture in the house. They grew the flax and sheared the sheep for the wool that their clothes would be made from. There was also a market day once a week, where farmers could sell their vegetables, butter, and milk. Once a year there would be markets for cattle and pigs to be sold, and people came from far away to attend them. At these markets, people did not always use money to buy things. Instead they bartered, paid in beaver furs, or used the Native American currency called sewant which was made of valuable shell beads.

In addition to helping their families with daily chores on the farm, many children were also given an education. Though some parents taught their children at home, others started school from the age of 7 or 8 years old. School was six days a week. The schoolmaster would have been a man, but there were also assistant teachers who were male or female. The funding for schoolmasters came from several sources, including the Dutch West India Company, mandatory subscriptions, and taxpayers, but the payment to the schoolmaster was made in wampum, beaver skins, wheat, peas, or rye. Parents were asked to pay to send their children to school, but if they did not have enough money, students could attend for free. Religion was the main topic that was taught, and the books used were often imported Bibles and psalm books. After the English took over the government in 1664, there was less attention given to schools. In addition, more people started immigrating to the area and there were not enough schools available. In the 18th century, older boys attended school only in the winter, because in the summer they were needed for farm work; it was the girls’ job to sweep out the schoolhouse, and it was the schoolmaster who crafted the quill pens for the students to write with.

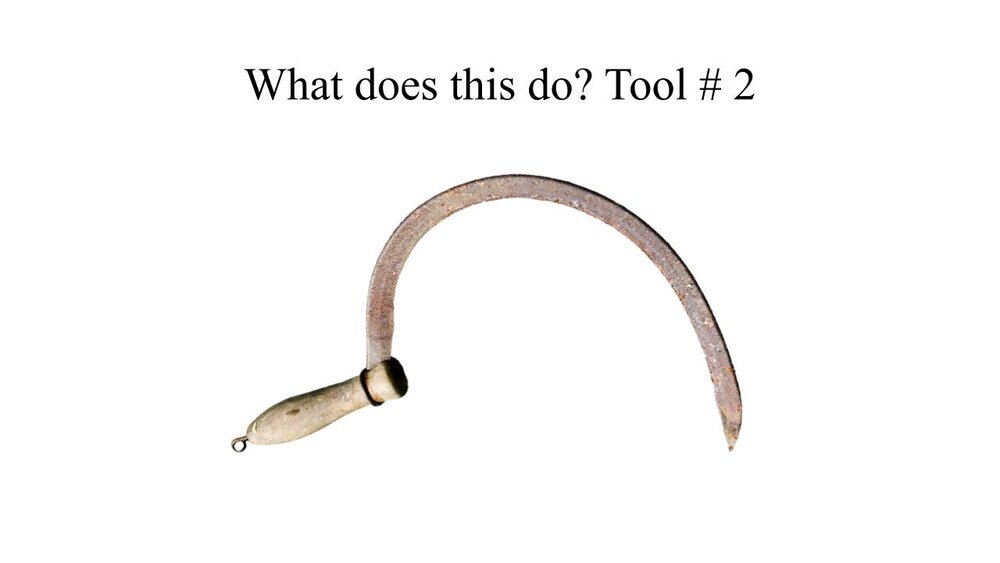

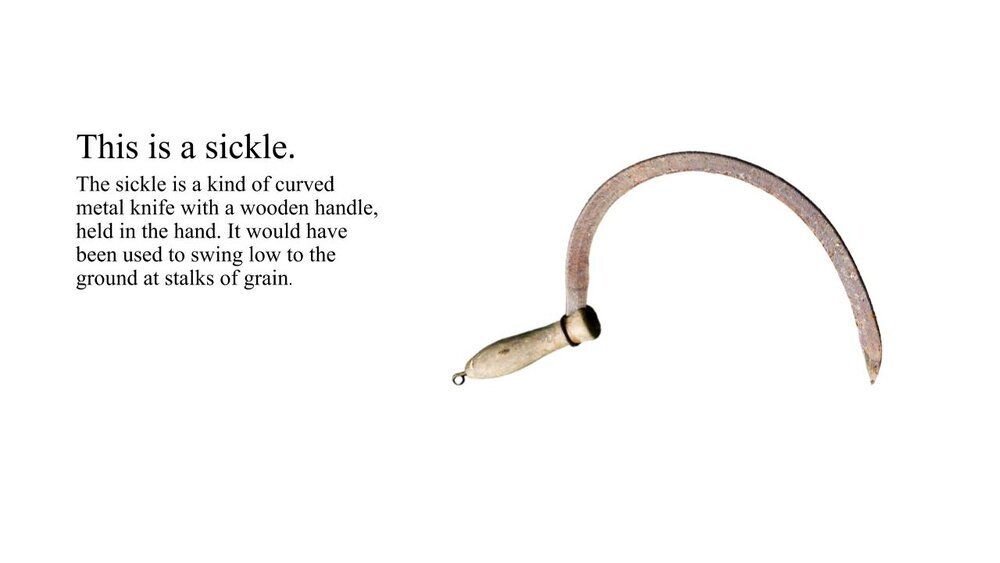

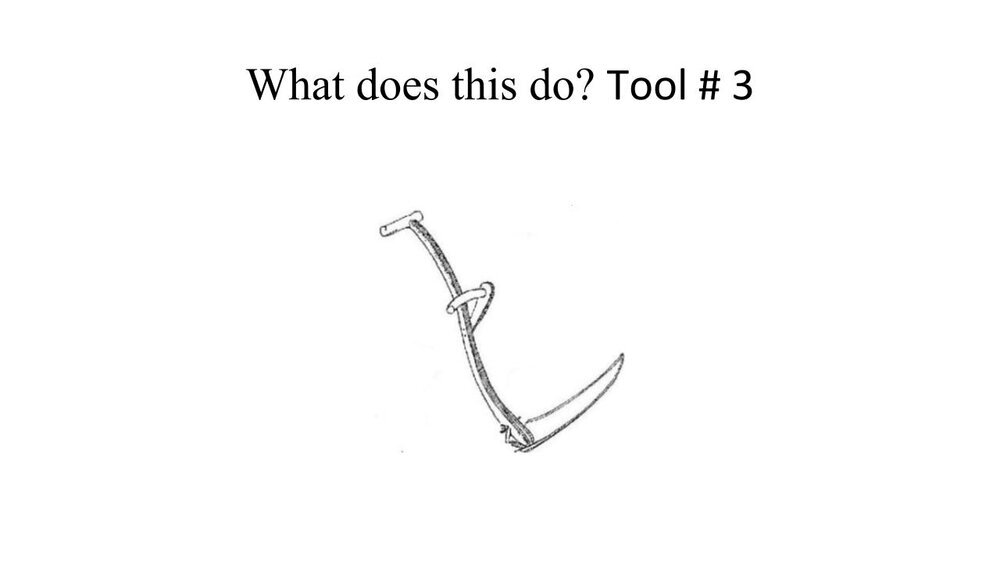

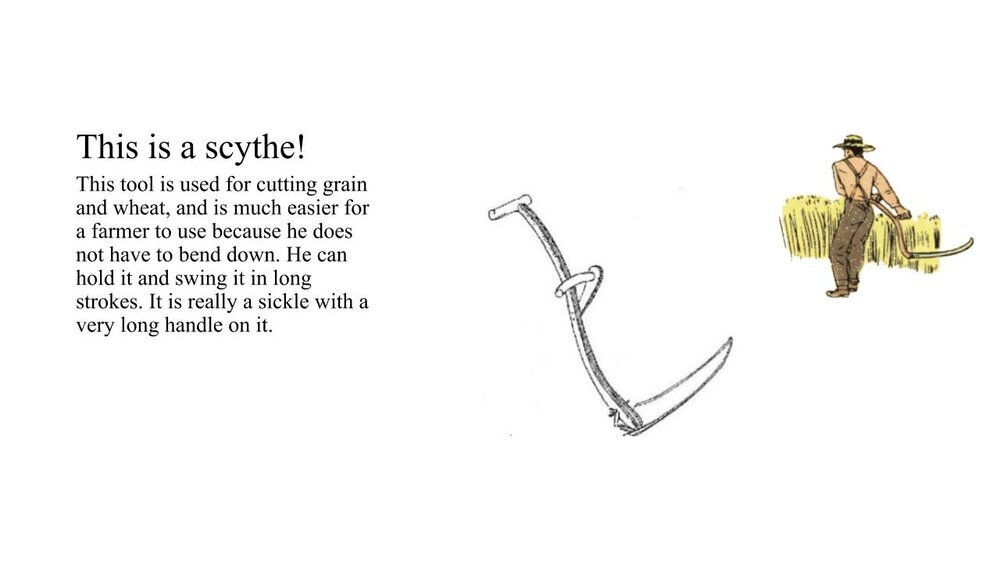

Student Activity: Farming Tool Quiz

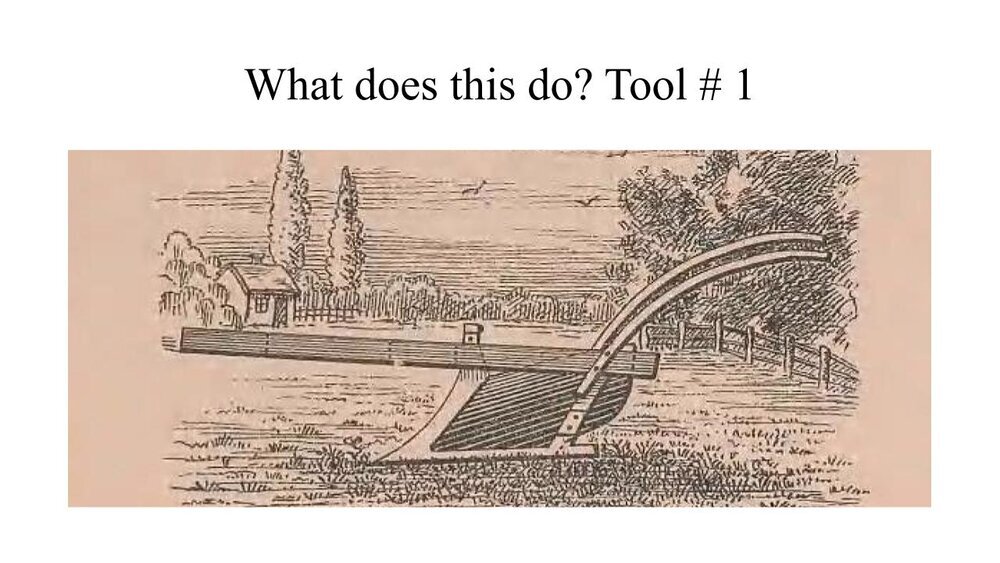

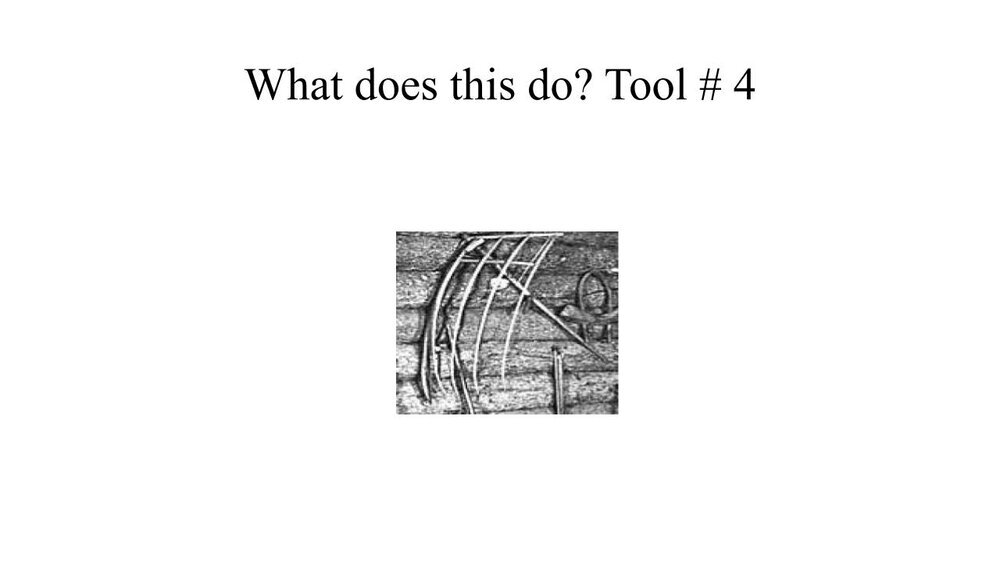

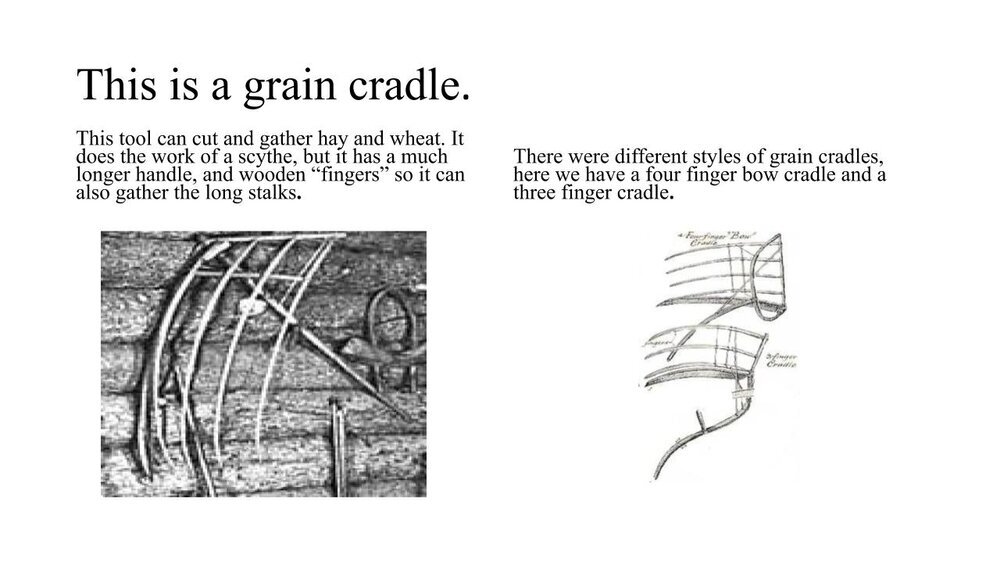

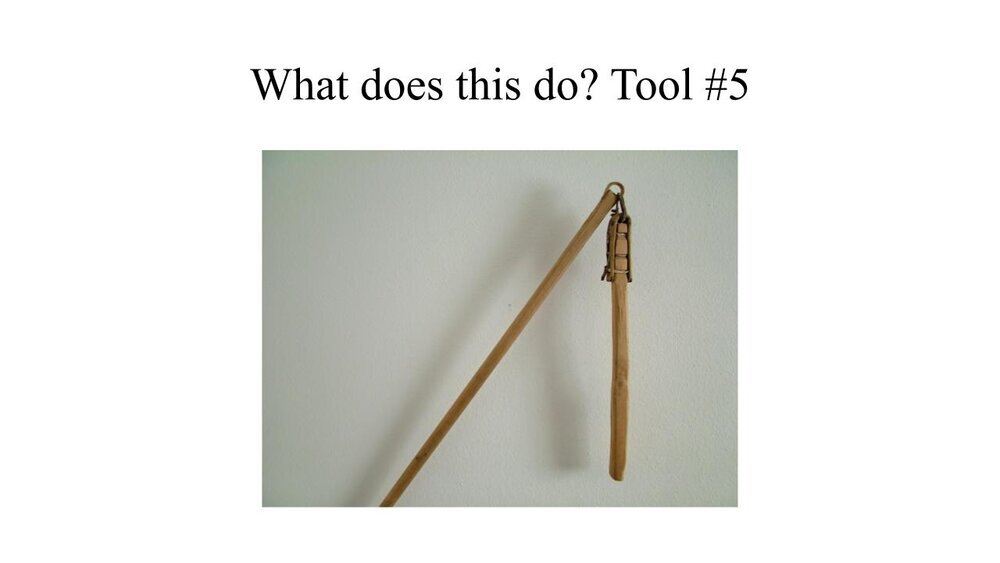

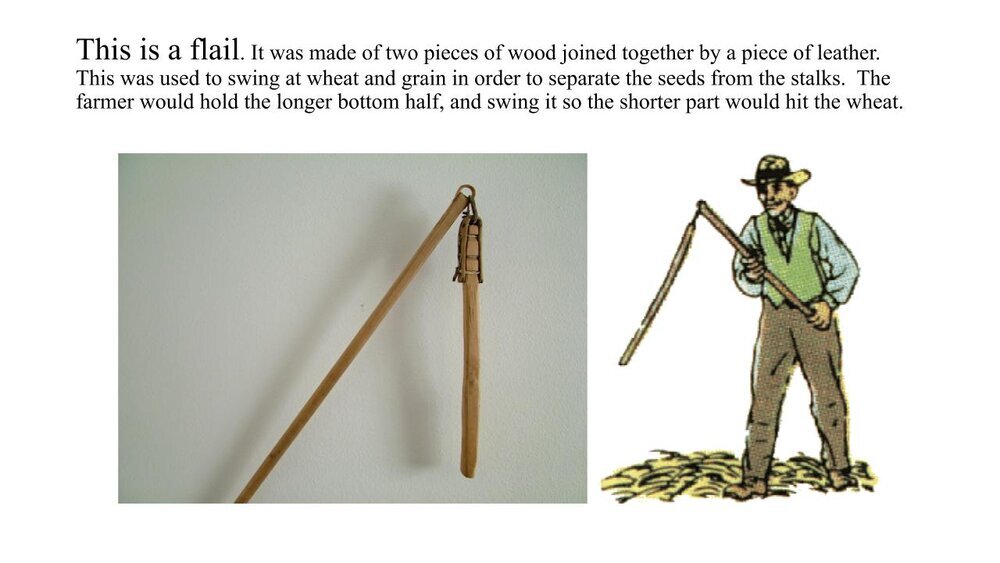

In living on a farm, do you know what tools you would have seen and used every day on the farm? Join us for a game to see if you can guess what the different implements were used for, to plant and grow food on the farm in the 17th and 18th centuries in New York.