EIGHT YEARS OF DOCUMENTED BOWNE HOUSE RESIDENTS’ INVOLVEMENT IN A NETWORK OF THE NEW YORK UNDERGROUND RAILROAD FROM 1842-1850

By Ellen M. Spindler, Collection Volunteer, and Charlotte Jackson, Bowne House Archivist

In the middle to the late years of the 1830s, abolitionism was transformed from a sentiment into an organized national movement, an “expanding array of anti-slavery societies whose members would provide the white rank and file of the Underground Railroad, linking them together with isolated cells and African American communities into a system that, in time, would spread across more than a dozen states.” [1] Although New York had abolished slavery by 1827, there were still many fugitive slaves from the South and other freedom seekers, such as free blacks at risk, who resided in or travelled through New York and were in need of assistance to make their way to freedom upstate or in Canada. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 strengthened the penalties of the previous Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, both of which permitted slave owners and bounty hunters to search for escaped slaves in free states, and made assistance to these freedom seekers even more perilous. [2]

Early Bowne House Residents’ Anti-Slavery Activities

Quaker settlements were among the early participants in abolitionist activities and then the Underground Railroad network. At its yearly meeting in 1768, the Flushing Meeting record reflects adoption of a committee report that "Negroes were by nature born free and when the way opens liberty ought to be extended to them..." [3] The New York Meeting finally issued a resolution in 1776 to ban the acceptance of contributions and services from those members who held slaves; thereafter those members were disowned. [4] By 1787, the New York Yearly Meeting certified that none of its members held slaves. [5] One former Bowne House resident who took a strong early stand was Robert Bowne, the founder of the Bowne & Co. printers. He was a founding member of the New York Manumission Society with Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and others in 1785. He also served as Trustee of the African Free School founded by the Manumission Society to educate free Blacks to assume their rightful place in society. [6]

In the next family generation, Robert Bowne’s niece Mary, who shared in the inheritance of the Bowne House, married the Quaker Minister Samuel Parsons. Long a sympathizer, Parsons became active in the abolition cause in the 1830s. [7] In 1834 Parsons wrote a letter to a Joseph Talcott advising that the New York Meeting was raising over $1,000 dollars to move up north free Southern blacks who were being threatened with a return to slavery. [8] In June 1837 a long denunciation of slavery by the New York Yearly Meeting appeared over his signature as Clerk of that body. [9] Thousands of copies were printed and distributed throughout the South. [10] Following the death of Mary (Bowne) Parsons in 1839, her share of the Bowne House passed to Samuel. The 1840 Federal Census indicates that the widower and his children then joined Mary's surviving sisters in the old homestead. According to one correspondent, Samuel Parsons spent his final days there poring over the proceedings of the World Anti-Slavery Convention with his sons. [11]

Finally, as circumstances worsened for blacks fleeing the South and trying to settle in New York City, Bowne house residents decided their faith and conscience required more direct action via participation in the Underground Railroad. In doing so, they faced potential prosecution due to the assistance they provided to fugitive slaves and other freedom seekers, such as free blacks at risk of kidnapping. However, as devout Quakers the family had survived social opprobrium and legal punishment before, and they had educated themselves well enough to know that slavery held even worse horrors.

The sons of Samuel and Mary Parsons were interested in abolition from an early age. In 1837 Samuel B. Parsons undertook a voyage to the West Indies with the English Quaker minister Joseph John Gurney to observe and report upon the newly emancipated society there. In his memoirs, Gurney reports that upon their return to the United States, he brought 19-year-old Samuel Parsons, Jr. and just one other man with him for intimate audiences with Senators Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John Calhoun and even President van Buren, to urge the cause of abolition. [12] Decades later, Samuel B. Parsons’ obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle stated that he “was a strong abolitionist and it was his boast that he assisted more slaves to freedom than any man in Queens County.” [13] His brother Robert B. Parsons' obituary in the Herald Tribune claimed that "before the Civil War, no fugitive slave who sought his assistance was turned away from his door." [14] Evidence from the Bowne House Archives shows that their younger brother William was also an agent of the Underground Railroad.

Bowne House Residents Become Involved in the New York Underground Railroad

At least three known Bowne House residents—Samuel Bowne Parsons (1819–1906), Robert Bowne Parsons (1821–1898), and William Bowne Parsons (1823–1856)—made documented connections with prominent activists involved in the Underground Railroad in New York. As sons of Samuel and Mary (Bowne) Parsons, and great-nephews of Robert Bowne, the brothers comprised the third generation of Bowne House residents to work for emancipation and racial justice.

Parsons family papers attest to contacts with known Underground Railroad agents over a period of at least eight years, from 1842–50. Their connections included the ministers Rev. Simeon S. Jocelyn and Rev. Henry Ward Beecher; philanthropists Lewis Tappan and Gerrit Smith; and New York Vigilance Committee officers Charles B. Ray and William Harned. During this period, Simeon Jocelyn ministered to the First Congregational Church of Williamsburgh and served as Vice-President of the New York State Vigilance Committee. Henry Ward Beecher was the fiery anti-slavery preacher at the Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn Heights. Lewis Tappan of Brooklyn was a co-founder and benefactor of Beecher's Plymouth Church and numerous other anti-slavery institutions. Gerrit Smith, a wealthy donor based in Peterboro, New York, near the Canadian border, served as President of the New York State Vigilance Committee and other anti-slavery organizations. Charles B. Ray was a black Manhattan minister and the director of the New York Vigilance Committee, described as the initial "hinge" upon which the Underground Railroad network in the City turned. Brooklyn Quaker William Harned was the Vigilance Committee's corresponding secretary and treasurer.

This tightly interwoven network of activists also connects Bowne House with at least two verified Underground Railroad sites in New York: the Gerrit Smith Estate in Peterboro and the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. [15] In 1842, a year after the death of Robert’s father Samuel Parsons, Lewis Tappan gave him a letter of introduction to an even more radical reformer, Gerrit Smith. Smith's upstate property is now a listed site with the National Park Service Network to Freedom, due to his involvement in purchasing the freedom of enslaved blacks, arranging their transport to Canada, and providing land upstate to those who were emancipated. Thus Robert B. Parsons already knew Lewis Tappan before 1847, when Tappan co-founded the Plymouth Church, whose first minister was Henry Ward Beecher. Plymouth Church itself is a listed Network to Freedom site, with evidence that fugitives were hidden in its tunnel-like basement until they could be transported to boats in the East River or moved elsewhere. [16] (Notably, Robert converted to the Congregational faith by 1851, when he raised funds to build a church in Flushing, armed with a written endorsement from Beecher himself.) [17]

Samuel Parsons inherited Mary (Bowne) Parsons' share of the Bowne House upon her death in 1839, and the 1840 Census indicates that the family had moved in with Mary's sisters. Upon Samuel's death his share passed to his children. Although his son Samuel B. Parsons moved across the street to the Parsons’ former residence following his marriage in 1842, his brothers Robert and William still resided at the Bowne House with their maiden aunts and unmarried sisters (as seen from the 1840 and 1850 federal censuses and a contemporaneous news article from 1843). [18] They only moved out to their own households when William married in 1851 and Robert married in 1857. Thus the public record establishes the brothers' residence at Bowne House during the period under discussion. [19]

1850 Federal Census, Flushing, Queens Co., New York

Documentation of Bowne Residents’ Involvement in the New York Underground Railroad Network

The collection Papers of the Parsons and Bowne Families in the Bowne House Archives contains several hundred items of Bowne and Parsons family correspondence and memorabilia, predominantly from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although these items were accessioned into the Museum’s collection in the 1980s, they were not systematically processed or read until recent years. Other Parsons and Bowne papers from the Bowne House were dispersed and now reside in other local Archives, such as the Queens Library and SUNY Stonybrook. Thus, our archivist and researchers continue to make significant new discoveries about the Bowne House’s involvement in anti-slavery activism and the Underground Railroad.

A. After his father Samuel Parsons’ death, Robert Bowne Parsons is introduced by Lewis Tappan to Gerrit Smith in a letter dated August 10, 1842

"My dear Sir,

The bearer is Mr. Rob't B. Parsons, of Flushing, son of the late excellent Samuel Parsons of the Society of Friends, and friend of Jos. Sturge. R.B.P. is a true man.

Affc'y yours, Lewis Tappan"

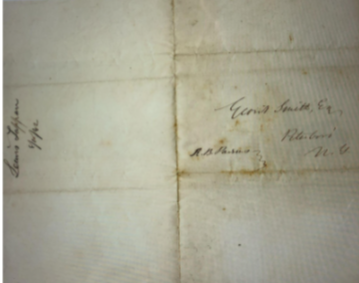

Lewis Tappan to Gerrit Smith, Aug. 10, 1842 (Bowne House Archives)

Reverse of Lewis Tappan to Gerrit Smith, 1942 (Bowne House Archives)

This brief letter of recommendation, written by Lewis Tappan to the wealthy activist Gerrit Smith at his Peterboro, N.Y. residence, was recently discovered in the Bowne House Archives. [20] In 1842, Robert B. Parsons was a youth of twenty-one who had recently lost both parents; the Parsons and Co. Nursery he now ran with his brothers was still in its early years. "Jos. Sturge" refers to the renowned English abolitionist and Member of Parliament Joseph Sturge, who successfully campaigned to end slavery throughout the British Empire and then founded the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society to abolish it worldwide. Sturge mentions two visits to the dying Samuel Parsons in his travelogue "A Visit to the United States in 1841," noting that "his sons are anxiously desirous of furthering the abolition cause on every suitable occasion"; he further quotes the elder Mr. Parsons as saying "Robert and I look at these publications [the Proceedings of the World Anti-Slavery Convention] as they appear, with deep solicitude." [21] Sturge was the chief organizer of this Convention, first held in England in 1840.

Peterboro is a notable historic location near Lake Ontario and the Canadian border, as the first meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society took place in the Smithfield Presbyterian church there in 1835. The delegates agreed to call for “universal and immediate emancipation.” That was the same year the Vigilance Committee of New York was formed downstate. Peterboro now hosts the National Abolition Hall of Fame and, as mentioned, the Gerrit Smith estate is a listed National Park Service Network to Freedom site. Lewis Tappan and Gerrit Smith are both inductees in the Hall of Fame. Both men were notable figures with national profiles, and there is only room to touch upon a few of their achievements here.

Lewis Tappan, Massachusetts Historical Society via Wikimedia Commons

Lewis Tappan (1788–1873) and his brother Arthur were wealthy philanthropists, silk merchants whose anti-slavery sentiments set them apart from the New York merchant class. In their partnership, Arthur chiefly held the purse-strings, while the gregarious Lewis handled networking and organizing. In 1833, the Tappans had co-founded and funded the influential American Anti-slavery Society (AAS) with William Lloyd Garrison; prominent early members included Frederick Douglas and Theodore Dwight Weld. AAS advocated an immediate and unconditional end to slavery, equal rights for freemen, and integrated schools and churches. This radical agenda proved particularly unpopular in New York City, which was heavily dependent on Southern trade; during the Abolition Riots of 1834, Lewis Tappan's house was looted by a white mob and his family's possessions burned in the street. [22]

One of his most public successes occurred shortly before he penned this letter. From 1839–1841 Tappan ran the Amistad Committee with Simeon Jocelyn and Joshua Leavitt, organizing the financial support, education, public relations, and legal defense for the African captives who had killed the captain of the slave ship Amistad, even recruiting John Quincy Adams to represent them before the Supreme Court. [23] Amid this very campaign, Tappan quit the AAS in a doctrinal dispute. In 1840 the Tappans and other conservative evangelicals, including figures associated with the New York Vigilance Committee like Henry Highland Garnet and the Rev. Theodore Wright, founded the rival American and Foreign Anti-slavery Society, or AFAS, which worked closely with the Vigilance Committee and solicited donations from British evangelicals. In 1846 Tappan would once again co-found a wildly influential organization, the inter-racial anti-slavery American Missionary Association (or AMA), which established schools throughout the world and was particularly influential in educating freemen after the Civil War. [24]

Lewis Tappan owned a horse that regularly carried fugitives from his “agent” at Havre de Grace, Maryland to Pennsylvania. [25] In January 1838, a runaway slave from Alabama arrived at Tappan’s home on New Year’s Day and was sent to England at Tappan’s expense. [26] In 1847, he helped fund the creation of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, now a listed Network to Freedom site as a station on the Underground Railroad. [27] On another occasion in 1849, he described finding 18 runaway fugitives at his office at 61 John Street which he shared with the New York Vigilance Committee; they were then transported by an agent of the Underground Railroad to Canada. [28] While he may have been less publicly vocal in his support for the Underground Railroad at the time, there can be no doubt he was privately involved in his financial support of these activities by others like Charles B. Ray with full knowledge. He began vocal and public support for the Underground Railroad in 1850, following the passage of the second Fugitive Slave Act.

Gerrit Smith (1797-1874), who saw opposition to slavery as a spiritual, moral and patriotic imperative, served four terms as President of the New York Anti-Slavery Society from 1836-39. By the end of his term, he was calling for abolitionists to defy the law and help fugitives escape to freedom.

Hon. Gerrit Smith of N.Y., ca. 1855-65 (Library of Congress)

During the 1840s and ‘50s, Smith became a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad. [29] In 1848 he served as President of the New York State Vigilance Committee, the statewide successor to the original New York City-based Vigilance Committee. That year he helped fund the "Pearl Affair," the most ambitious peaceful escape attempt in Underground Railroad history, in which 77 slaves fled Washington, D.C. on the schooner Pearl. His ambitious "Timbuctoo" settlement in the Adirondacks gifted 120,000 acres of land to 3,000 formerly enslaved black homesteaders so that they could gain access to the franchise. [30] Although the experiment ultimately proved impracticable, a newspaper saved by the Parsons among the family papers at Bowne House reports on another generous mass grant by Smith, this time to impoverished whites. [31] Later, as one of the “Secret Six,” Smith contributed to John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, for which Jefferson Davis attempted to have him hanged alongside Brown. [32]

Robert Bowne Parson’s letter of introduction includes a letterhead with a kneeling slave engraved by fellow abolitionist Patrick Reason, one of the first black American engravers. Reason was a graduate of the same African Free School, founded by the Manumission Society, for which Robert Bowne served as a Trustee. The image, featuring the inscription "Am I not a man and a brother?" was one of the most popular instances of anti-slavery iconography at the time. (There is also a version featuring a female supplicant and the caption "Am I not a woman and a sister?") [33] This interesting detail shows that Tappan understood the need for abolitionists to patronize Black businesses, so freemen could support themselves.

This letter establishes Robert Bowne Parsons’ early statewide contacts with some of the wealthiest donors involved who were linked to the Underground Railroad. We cannot say whether the purpose of his introduction was to vouch for Robert’s credentials as a liaison to the Queens Quaker community following his father’s death, to raise funds since Gerrit Smith was known to donate money to anyone with a plausible plan to help free enslaved blacks, or to establish an upstate destination for freedom seekers on their way to Canada, or for free blacks seeking to peaceably settle upstate. In 1847, Gerrit Smith gave deeds to mostly former slaves in New York City, including 215 in Queens County. It should be noted that these were the relatively early days of the Underground Railroad network in New York, five years before Plymouth Church in Brooklyn was founded, but seven years after the original Vigilance Committee in New York City had commenced its operations. This letter underscores the critical role that character references, personal associations, and trust played in recruitment for the cause.

B. Robert & Samuel’s Intimate Acquaintance with Henry Ward Beecher

The Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887) served as the first minister of Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims in Brooklyn, now a landmarked building in Brooklyn Heights, close to the modern-day Brooklyn Bridge Park. He is said to have “spearheaded and symbolized anti-slavery activities there.” [34] The church became known as “the Grand Central Depot'' of the Underground Railroad. Already known as an opponent of slavery, Beecher addressed this topic in his very first sermon.

He became known in 1848 for one of his first anti-slavery acts. After 87 slaves were sold in Washington, D.C. following a failed escape attempt on the Underground Railroad funded by Gerrit Smith, he arranged for the purchase of two teenage girls. His action helped inspire his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe to write the famous Uncle Tom's Cabin, which first appeared in Lewis Tappan's journal The New Era. He frequently held “mock auctions” to encourage congregants to buy the freedom of slaves, a direct challenge to the institution of slavery in Southern states at the time.

Samuel Bowne Parsons' obituary in the New-York Tribune wrote that “Chauncey M. Depew, Horace Greeley, Henry Ward Beecher, George William Curtis and Bayard Taylor were numbered among Mr. Parsons’s intimate friends,” confirming his friendship with Rev. Beecher among other prominent abolitionists. [35] His brother Robert Bowne Parsons may have been even closer to Beecher, as he became a Congregationalist himself. Robert's efforts to fund a new Congregational Church in Flushing received a personal letter of endorsement from Beecher, quoted in an unpublished history of the Church: "I heartily wish that the bearer, Robert Parsons of Flushing, may find favor in the sight of all to whom these may come. He is too modest to be a good beggar, but he is a capital man and the enterprise which he (though born a Friend) with other gentlemen is endeavoring to achieve is worthy of liberal consideration and aid." [36] Possibly they collaborated on the Underground Railroad as well: Robert's obituary in the Tribune stated that “before the Civil War no fugitive who sought his assistance was turned away from his door.” [37]

C. Charles B. Ray and William Harned from the New York State Vigilance Committee write fundraising letter of July 28, 1849 to Robert Bowne Parsons appealing for assistance in raising and safeguarding funds

As previously reported, we have also confirmed a letter in the Archives of Queens Library Central from William Harned to Robert Bowne Parsons dated July 28th, 1849, asking Parsons on behalf of himself and Charles B. Ray to provide “aid and comfort” to a man they had selected named Robert Edmund and to assist him to his fundraising efforts among “your villagers” and “those sympathetic with the slave” in “adjacent towns & neighborhoods.” [38]

Will Harned to Robert B. Parsons, July 28, 1849. (Queens Library Archives)

Transcript of Letter from Will Harned to Robert B. Parsons, dated July 28th 1849

Esteemed friend,

Our Vigilance Committee must have money, or give up our business. In our emergency, we are under a necessity of employing every lawful & honorable means of raising funds. We have concluded to send out our friend Robert Edmund, of whom we hear a good report, to make an appeal in our behalf to all who have a heart to sympathize with the slave. Chas (Charles) B. Ray & I have concluded to let him commence among your villagers. Will you not give him all the “aid & comfort” you can? And see that he is put on the track of every one who will be likely to sympathize with the object of his mission? In laboring in your vicinity, I shall request him to deposit any surplus funds he may collect with you. You will, I hope be able to counsel him as to his operations in adjacent towns & neighborhoods.

Yours truly, but in mine Haste Will Harned

Charles B. Ray (1807-1886) was a well-known Methodist, and then Congregationalist minister of Bethesda Congregational church, and activist at the time. He became involved in the American Anti- Slavery Society in 1833, and then in 1843 the Vigilance Committee of New York, serving on both the Executive Board and as Corresponding secretary. He was also the editor of the Colored American. The Vigilance Committee of New York, founded on November 20, 1835, was engaged in numerous anti-slavery activities, including publicizing missing persons, assisting fugitives, and raising funds for the legal defense of those in need. Their highest priority was the epidemic of kidnappings. [39, 40, 41] They are believed to have had about 100 members who made regular contributions. The Committee has been described as the “hinge” upon which the Underground Railroad turned in New York. [42]

The Committee was run primarily by blacks, but funds were solicited both from blacks and wealthy sympathetic whites who were able to make significant contributions, including major donors Lewis Tappan and Gerrit Smith. Later in 1847, after one founding member of the Committee died and another resigned, it was reconstituted as the New York State Vigilance Committee, with a similar purpose to the original New York City Committee, but with contacts throughout the state; according to the Baltimore Sun, it “is the celebrated Underground Railroad.” Gerrit Smith was President and Charles Ray served on the executive board. [43] Simeon Jocelyn served as Vice-President. William Harned (initially a Quaker and then a Congregationalist) was the corresponding secretary and treasurer. [44] The State Committee had more whites in leadership and was less radical in its methods than the original Committee had been under the firebrand David Ruggles, who was known to board suspected slave ships in the New York harbor and raise crowds to storm jails where kidnapped blacks were held. Ruggles had also carried on a "name and shame" campaign against local officials or other prominent people who aided bounty hunters. The State Committee chose to operate in a less confrontational way and to focus its activities on the Underground Railroad itself. [45]

The author of this 1849 letter, William Harned, was also an associate of Lewis Tappan. A fund appeal by the Vigilance Committee in 1849 noted their need for more donations, a perennial problem. Harned’s letter referring to Ray and the Vigilance committee seems to imply that Robert Bowne Parsons may have been a primary contact for them in Queens in their fundraising efforts. The suggestion that he is aware of everyone, not only in Flushing but in the surrounding area, who sympathizes with the cause speaks to the depth of his involvement.

Charles B. Ray was known to have held several gatherings in his home on Baxter Street that included some of the most influential activists of the day, including Lewis Tappan, Simeon Jocelyn (the sender of an 1850 letter to William B. Parsons requesting his help in hiding a fugitive, further discussed below), and Joseph Sturge, the celebrated English Quaker discussed in connection to the Lewis Tappan letter. [46] Charles B. Ray was quoted as saying “he regularly dropped off fugitive slaves at Plymouth Church” which gave them aid and temporary shelter under the direction of its famous minister Henry Ward Beecher. [47]

It is possible that Robert Bowne Parsons first met Sturge and Beecher at Charles B. Ray’s home; conversely, he may have entered their circle through his father’s acquaintance with Sturge. We do know that Sturge was respected enough within this circle that his friendship was used as a reference in Lewis Tappan’s letter of introduction for Robert Bowne Parsons to Gerrit Smith. Either way, Parsons clearly would have known the purpose of fundraising for the Vigilance Committee. The fact that he was asked to safeguard the funds shows not only an extraordinary level of trust placed in him, but his willingness to assume significant risk in providing assistance. Since Robert B. Parsons still resided in the house at the time of receipt of this letter, it places the Bowne House squarely in the midst of Queens fundraising for the New York Underground Railroad.

Interestingly, a Holmes electrical security alarm was installed in Bowne House circa 1863, not common during those times. [48] Although apparently not contemporaneous with this letter, it may have been used to safeguard funds or confidential documents at the house. The concealed niche shown below, found in a back room at the house, is typical of measures used by Quakers to conceal valuables. As they refused to pay levies for militia, the pacifist Friends were subjected to frequent raids and confiscations of property during the colonial period and throughout the Revolutionary War. According to historian Kathleen Velsor, who has made an extensive study of Friends on Long Island and their involvement in the Underground Railroad, hidden compartments for valuables and people are common in historical Quaker homes due to their own history of persecution. [49]

Indented “safe” in a rear room at the Bowne House; photo by Stefan Dreisbach-Williams

D. Simeon Jocelyn’s letter of September 28, 1850 appeals to William B. Parsons for assistance in harboring a freedom seeker

Written by a prominent activist Simeon Smith Jocelyn, who was Vice-President of the New York Vigilance Committee at the time, this document attests directly to the Parsons family’s role as conductors in the Underground Railroad in Flushing. For a detailed exploration of this letter, see also the article "A Ticket for the Underground Railroad" on the Bowne House website.

The letter reads as follows:

“Williamsburgh, Sept 28th 1850.

William Parsons, Esq.

Dear Sir, I commend unto thee this colored brother, who will tell you so much of his story as is necessary to guide your action for his welfare. Williamsburgh is too near the city for his safety. If he can be kept for a few days perfectly unobserved in your neighborhood, he may after the hunters shall have returned take passage east or north as may be deemed advisable. This is a strong case and great care and caution is required. Having received injury in my arm by railroad accident, I am dependent on my daughter to write this letter.”

Truly yours, S.S. Jocelyn”

Simeon Jocelyn to William Parsons, Esq., Sept. 28, 1850. (Bowne House Archives)

Simeon Jocelyn to William Parsons, Reverse side and Address (Bowne House Archives)

Simeon Smith Jocelyn (1799–1879) was already a prominent person in the New York Underground Railroad at the time of this letter. Jocelyn was a social reformer closely allied to William Lloyd Garrison and brothers Arthur and Lewis Tappan. A vocal abolitionist and activist, he ministered to a predominantly Black congregation in Williamsburgh, Brooklyn, and had served as Vice-President of the New York State Vigilance Committee since its formation in 1847.

Simeon S. Jocelyn (Massachusetts Historical Association)

Jocelyn presided over the Vigilance Committee’s annual meetings in 1848, 1849, and 1850. As previously discussed, the Vigilance Committee was regarded as the underground "Grand Central Station," in charge of dispatching freedom seekers via the most opportune route and providing them with the funds and provisions they would require for their journey to safety.

A native of New Haven, Simeon Jocelyn started several black schools there, as well as New Haven’s first church for black residents, where he preached while training black ministers to take over. He also financed Trowbridge Square, a racially integrated affordable housing development. Jocelyn’s vision of founding a “Black Yale” in New Haven to educate emancipated slaves foundered when he presented it at a town meeting just weeks after Nat Turner’s rebellion; his proposal was resoundingly defeated by a vote of 700 to 4, and his home was later stormed by a stone-throwing mob. However, Jocelyn is perhaps best known for his role in the Amistad Affair. Jocelyn was instrumental in lobbying and fundraising on behalf of the imprisoned Africans, who had mutinied after being illegally kidnapped and held captive on the slave ship Amistad. [50]

By 1850, Simeon had settled in New York, where he lived with his family in Williamsburgh and presided over his Congregationalist Church, while serving as President with Lewis Tappan of the anti-slavery American Missionary Society. Williamsburgh (as it was then spelled) boasted a sizable population of free people of color with multiple Black congregations that, like the community of Flushing, formed a critical nexus in the Underground Railroad.

Due to Simeon’s prominence and positions held, he would have likely interacted with both Charles B. Ray and Robert B. Parsons and been aware of Robert’s fundraising efforts. Jocelyn's role took on particular urgency after the Fugitive Slave Act was enacted on September 18th of 1850. The law suspended the right of habeas corpus for Northern Blacks and required citizens of free states to actively assist slave hunters, on pain of prison time and draconian fines. Mere days later, a free resident named James Hamlet was abducted off the streets of Manhattan by bounty hunters and imprisoned in Baltimore, only rescued when members of the Black community raised funds to purchase his freedom. This notorious incident surely forms the backdrop to Jocelyn’s letter, written just ten days after the law was signed. [51]

As for the letter’s recipient, William Bowne Parsons was the younger brother of Samuel and Robert Bowne Parsons, who were both already directly involved in the Underground Railroad. Judging from the formality of address, Mr. Jocelyn may not have been personally acquainted with William Parsons; however, it seems likely that the two had corresponded before, as Jocelyn feels the need to explain why the penmanship in this missive differs from his usual hand. He also must have gained a high regard for Parsons’ judgment and integrity, given his comment about “great care and caution” being required.

As for the bearer himself, the “colored brother” who carried this letter on his journey to freedom, sadly we know nothing of his identity, nor his story. We cannot be sure where in the neighborhood this freedom seeker was hidden. Runaway slaves and their hosts often favored remote outbuildings over family homes on trafficked streets. A shed or greenhouse within the Parsons Nursery might have been ideal. According to Samuel Bowne Parsons' obituary, in his later years he was often overheard reminiscing about concealing fugitives in his cellar and stable and then transporting them to the shore in Whitestone. However, it seems likely that multiple hiding places and escape routes would be used, depending on the circumstances of each case.

E. The Role of the Parsons Commercial Gardens & Nursery

All of these Bowne House interactions occurred while Samuel and Robert Bowne Parsons owned and operated the Parsons Nursery, with the assistance of their younger brother William. The Nursery commenced around 1837-40, thus overlapping with the early days of an organized Underground Railroad in New York City, and was operated in part on the approximately 250-acre Bowne Farm. In 1843 it comprised 30 acres in Flushing, with other land available elsewhere. [52] By 1852 it comprised over 75 acres of plantings. Significantly, Samuel Bowne Parsons’ obituary in the Flushing Times recounts his reminiscences of concealing freedom-seekers in his cellar and stable and then driving them to Whitestone where he had engaged a boatman to enable their escape. [53] This suggests that the Nursery provided cover for the family's Underground Railroad participation.

Maps of Flushing from circa 1841 and 1852 show the area of the Bowne Farm and the Parsons Commercial Gardens & Nursery largely adjacent to the Bowne house. The elder Samuel Parsons’ home lot, inherited by Samuel B. Parsons in 1841, lay directly north of Bowne House across Broadway (now Northern Boulevard), at the end of Bowne Avenue (now Bowne Street). Samuel Parsons also owned a tract of marshland northwest of Whitestone Avenue, fronting onto Spring Lane and backing on to a spring that flowed into the Flushing Mill Pond, which led into Flushing Creek and then Flushing Bay. [54]

The more detailed 1852 map shows the Parsons Nursery occupying 75 acres adjacent to Bowne House, with over half of Samuel B. Parson's personal 45-acre lot also dedicated to plantings; the Bowne Farm to the south and east occupies 150 acres, while the marshland still appears undeveloped. [55]

Thus the family had extensive land holdings in close proximity to Flushing Creek (then as now, a short walk away) and Flushing Bay. The Nursery was also convenient to the Flushing Steamboat Landing and various stations of the Long Island Railroad which commenced in 1836. Recalling Samuel B. Parsons' obituary, a 1940 map of the Bowne Farm, based on an original from the 1850s, even shows an outbuilding labeled "Office/Packing Shed" on Nursery grounds, and depicts Whitestone Avenue and Whitestone Road both leading north off the estate. While the Parsons Papers show who connected the Parsons to the Underground Railroad, the maps hint at how they connected.

Map of the Bowne Farm (annotated) from original circa 1850s (Bowne House Archives)

Our ongoing research at Bowne House is studying possible locations for concealment and attempting to establish routes of escape to the east or north as mentioned in the letter. One route associated with Hicksite Quaker Meetings, documented by Prof. Kathleen Velsor of SUNY Old Westbury, leads north through Westchester County at least as far as Nine Partners. [56] Nine Partners was home to the famed Quaker boarding school whose alumni include Lucretia Mott- and the Parsons brothers' aunt, Eliza Bowne, who lived with them at Bowne House during this period. On the other hand, Samuel Bowne Parsons' wife, Susan Howland, came from New Bedford, Massachusetts, one of the most hospitable Underground Railroad destinations and one where many freedom-seekers decided to settle permanently. The Quaker historian Rufus Jones believed that Susan's father, George Howland, was involved with the Underground Railroad there; it is a matter of record that George employed the young Frederick Douglas, who wrote of him in his autobiography, and his former home was recently included in the New Bedford Historical Society's proposed "Abolition Row" historic district. Thus, New Bedford might have been one possible destination to the "east."

Given their evident commitment to the freedom seekers' cause, it is likely that the Parsons continued their involvement with the Underground Railroad beyond the 1850 incident until the Civil War, although given the spotty nature of the documentary record (a given, considering the risks involved) details are lacking. What we can now say with confidence is that between 1842 and 1850, the three Parsons brothers enjoyed the trust of prominent members of New York's anti-slavery movement, were actively involved in raising funds to assist freedom seekers, and helping to harbor them in their Flushing Queens neighborhood, likely on their property. As with their famous ancestor's struggle for religious liberty and toleration, the moral courage of their actions is highly commendable and should not be forgotten.

SELECTED SOURCES

On Gerrit Smith:

Dann, Norman. Practical Dreamer: Gerrit Smith & the Crusade for Social Reform. Edited by Brian L. McDowell. Hamilton, New York: Log Cabin Books, 2009.

“Aboard the Underground Railroad - Gerrit Smith Estate and Office.” National Park Service. Accessed June 18, 2021.

"Gerrit Smith Estate National Historic Landmark." Smithfield Community Association. 2021.

On Lewis and Arthur Tappan:

Tappan, Lewis. The Life of Arthur Tappan. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870.

Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War against Slavery. Baton Rouge, LA.: LSU Press, 1997.

On Charles B. Ray and William Harned:

Ripley, C. Peter et al., eds., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. II, Canada, 1830- 1865 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p. 113-8; Letters written by Henry Bibb, 1850-1851, fn. 9, accessed May 31, 2021.

Wells, Jonathan Daniel, The Kidnapping Club, Wall Street, Slavery and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War, New York: Bold Type Books, 2020.

Work, M.N., "The Life of Charles B. Ray." The Journal of Negro History 4, no.4 (1919): 361-371. Accessed May 20, 2021.

On Henry Ward Beecher:

"Social Justice: The Underground Railroad." The Plymouth Church. 2000.

"Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims: Aboard the Underground Railroad." National Park Service. Accessed June 18, 2021.

On Simeon S. Jocelyn:

Dugdale, Anthony, J. J. Fueser, and J. Celso De Castro Alves. Yale, Slavery, and Abolition. Publication. New Haven, CT: Amistad Committee, 2001. PDF at <http://www.yaleslavery.org/YSA.pdf>

McQueeney, Mary. “Simeon Jocelyn, New Haven Reformer.” Journal of the New Haven Colony Historical Society 19, no. 3 (1970): 66

On the Underground Railroad in New York:

Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan, The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement. New York: Amistad, 2005.

Braithwaite, Jamila Shabazz. “The Black Vigilance Movement in Nineteenth Century New York City.” Master’s Thesis. CUNY City College of New York, 2014.

Driscoll, James, Derek M. Gray, Richard J. Hourahan, and Kathleen G. Velsor. Angels of Deliverance: The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island, and Beyond. Edited by Wini Warren. Flushing, New York: Queens Historical Society, 1999.

Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2015.

Velsor, Kathleen G. The Underground Railroad on Long Island: Friends in Freedom. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2013.

Wells, Jonathan Daniel, The Kidnapping Club, Wall Street, Slavery and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War, New York: Bold Type Books, 2020.

The Fugitive Slave Act:

United States Fugitive Slave Law. The Fugitive slave law. Hartford, Ct.?: s.n., 185-?. Hartford, 1850. Pd

American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and Lewis Tappan. The Fugitive Slave Bill, its History and Unconstitutionality: with an account of the seizure and enslavement of James Hamlet, and his subsequent restoration to liberty. Pamphlet. New York: William Harned, 1850. Digitized by Haithi Trust.

Cobb, Jeffrey Owen. “James Hamlet, Williamsburg Resident, First Victim of the Fugitive Slave Law.” Historic Greenpoint (blog), April 30, 2014.

___________________________

[1] Fergus M. Bordewich, Bound for Canaan, The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America’s First Civil Rights Movement (New York: Amistad, 2005), 153.

[2] An Act to amend, and supplementary to, the Act entitled "An Act respecting Fugitives from Justice, and Persons escaping from the Service of their Masters", approved February twelfth, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-three, amended September 18, 1850 (FUGITIVE SLAVE ACT), Public Law 31-60, U.S. Statutes at Large 9 (1850): 462.

[3] Rufus Matthew Jones, Isaac Sharpless, and Amelia Mott Gummere, “May 28, 1768, The New York Yearly Meeting," in The Quakers in the American Colonies, (London: Macmillan and Co., 1911), 257.

[4] Ibid., 258.

[5] "Quakers and Slavery Resources : Timeline," from Quakers and Slavery, online exhibit from Bryn Mawr College Library Special Collections, 2011, https://web.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/speccoll/quakersandslavery/resources/timeline.php

[6] Minutes of the Manumission Society of New-York, January 25, 1785-November 21, 1797, New-York Manumission Society Records, MS 1465, New York Historical Society. Accessed via the Shelby White and Leon Levy Digital Library, https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A133001#page/2/mode/2up

[7] Samuel Parsons, Diary, (unpublished manuscript, no date), Vol. 2, Parsons Family Collection: Miscellaneous Personal and Business Papers, Queens Library Archives, Jamaica, New York, U.S.A., quoted in James Driscoll, Derek M. Gray, Richard J. Hourahan, and Kathleen G. Velsor, Angels of Deliverance, The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island and Beyond, ed. Wini Warren (Flushing, N.Y.: Queens Historical Society, 1999), 73-75. Note: see footnotes 20-22, 25 and 27 for quoted extracts.

[8] Joseph Talcott, The Memoirs of Joseph Talcott (Auburn, N.Y.: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 1855), 271-73, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/LaxWacPNE5MChl=en&gbpv=1

[9] An Address to the Citizens of the United States of America on the Subject of Slavery, from the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (called Quakers) Held in New-York. (New York: New-York Yearly Meeting of Friends, 1837), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t9j38vv6r&view=1up&seq=11

[10] Warren, Angels of Deliverance, 75.

[11] Joseph Sturge, A Visit to the United States in 1841 (Bedford, MA.: Applewood Books, 2007), 136-37. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Visit_to_the_United_States_in_1841/J6rShVFuZ0cC?hl=en&gbpv=0 Reprint of the 1842 American edition by Dexter S. King, Boston, MA.

[12] Joseph John Gurney, Memoirs of Joseph John Gurney, with Selections from his Journal and Correspondence, 3rd, edition, ed. Joseph Bevan Braithwaite (London and Kent: Headley Brothers, 1902), 373-76.

[13] Obituary of Samuel B. Parsons, Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, N.Y.), January 4, 1906. https://bklyn.newspapers.com/clip/26524140/samuel_b_parsons_obit/.

[14] Obituary of Robert B. Parsons, New York Daily Tribune, November 6, 1898, quoted in James Driscoll, “Flushing in the Early Nineteenth Century,” Angels of Deliverance: The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island, and Beyond, ed. Wini Warren (Flushing, New York: Queens Historical Society, 1999), 60.

[15] “Explore the Underground Railroad,” National Park Service, last modified April 22, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/undergroundrailroad/explore-ugrr-sites.htm. See Network To Freedom Listings, searchable by state.

[16] “Social Justice: The Underground Railroad,” Plymouth Church, 2020, http://www.plymouthchurch.org/underground-railroad

[17] Warren, Angels of Deliverance, 83.

[18] A.B. Allen, “Commercial Nursery and Garden of Messrs. Parsons & Co.,” American Agriculturist (1842-50), August 1843, 2, no. 5, American Periodicals, 130.

[19] Copies of U.S. Federal Census Records for Flushing, Queens Co., New York, 1800-1890, AC# 2018-02, Folder 4 Box 3, John Bowne and Early Flushing Research Collection, Bowne House Archives, Flushing, New York, U.S.A.

[20] Letter of introduction: Lewis Tappan, New York, to Gerrit Smith, Esq, Peterboro, re: Robert Bowne Parsons, August 10, 1842, AC #2008.578, Box 1, Folder 16, Parsons and Bowne Family Papers, Bowne House Archives, Flushing, New York, U.S.A.

[21] Sturge, Visit to the United States, 136-37.

[22] Karl Zinmeister, "Abolition: A Case Study," in What Comes Next? Four Case Studies on Changing Society Through Civil Action (Washington, D.C.: The Philanthropy Roundtable, 2016), 64-79, philanthropyroundtable.org

[23] Douglas O. Linder, “Stamped With Glory: Lewis Tappan and the Africans of the Amistad,” Famous Trials (web site), University of Missouri Kansas City School of Law, 1995-2021, https://famous-trials.com/amistad/1204-tappanessay

[24] Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War against Slavery (Baton Rouge, LA.: LSU Press, 1997). Reprint of 1969 edition from the Press of Case Western Reserve University.

[25] Foner, Eric, Gateway to Freedom, The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, (2015), 56.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Plymouth Church, “The Underground Railroad.”

[28] Foner, Gateway to Freedom, 89. See also 66 and 85.

[29] “Aboard the Underground Railroad - Gerrit Smith Estate and Office,” National Park Service, accessed June 18, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/underground/ny3.htm

[30] “Timbuctoo,” in Adirondack History Guide, Adirondack.net, Accessed May 31, 2021, https://www.adirondack.net/history/timbuctoo/

[31] “A Christian Philanthropist,” Flushing Journal, 1849. Collection AC# 2019-01, Box 7, Folder 3, Item AC# 2008.737, Parsons and Bowne Family Papers, Bowne House Archives, Flushing, New York, U.S.A. Note: date of issue currently undetermined due to poor condition of original.

[32] Edward Renehan, The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired With John Brown (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1997), 11-18; 141-63

[33] Patrick H. Reason, Kneeling Slave, 1835, engraving, unknown dimensions. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Patrick_Reason_engraving.jpg.

[34] Plymouth Church, “The Underground Railroad.”

[35] Obituary of Samuel B. Parsons, New-York Tribune, January 5, 1906. Library of Congress: Chronicling America - New York Tribune Archive. Article appeared on page 8 of issue consulted.

[36] Unpublished bulletin on the history of the First Congregational Church of Flushing, November 11, 1944, quoted in James Driscoll, “Flushing in the Early Nineteenth Century,” in Angels of Deliverance: The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island, and Beyond, ed. Wini Warren (Flushing, New York: Queens Historical Society, 1999), 83.

[37] Obituary for Robert B. Parsons, New York Daily Tribune, November 6, 1898, quoted in James Driscoll, “Flushing in the Early Nineteenth Century,” in Angels of Deliverance: The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island, and Beyond, ed. Wini Warren (Flushing, New York: Queens Historical Society, 1999), 60.

[38] Letter from Will Harned to Robert B. Parsons, July 28, 1849, Control #P-7b, Box 281H, Folder 7, Parsons Family Collection: Miscellaneous Personal and Business Papers, Queens Library Archives, Jamaica, New York, U.S.A.

[39] Jonathan Daniel Wells, The Kidnapping Club: Wall Street, Slavery and Resistance on the Eve of the Civil War (New York: Bold Type Books, 2020), 223.

[40] Foner, Gateway to Freedom, 88-90.

[41] M. N. Work. "The Life of Charles B. Ray." The Journal of Negro History 4, no. 4 (1919): 361-71. Accessed May 20, 2021. doi:10.2307/2713446.

[42] Bordewich, Bound for Canaan, 171.

[43] Tom Calarco, People of the Underground Railroad (Westport, CT.: Greenwood Press, 2008), 134-35, 211-12; Baltimore Sun, May 12, 1848, quoted in Foner, Gateway to Freedom, 89. Note: cited at fn. 49.

[44] Foner, Gateway to Freedom, 89; C. Peter Ripley, ed., The Black Abolitionist Papers, Vol. II: Canada, 1830-1865 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 113-8; Letters written by Henry Bibb, 1850-1851, fn. 9.

[45] Jamila Shabazz Braithwaite, The Black Vigilance Movement in Nineteenth Century New York City, Master’s Thesis, CUNY City College of New York, 2014. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/264/

[46] Work, Life of Charles B. Ray, 361.

[47] Plymouth Church, “The Underground Railroad.”; Work, supra, 362.

[48] Walter Richard Wheeler, The Bowne House: An Historic Structures Report. (Rensselaer, New York: Hartgen Archaeological Associates, 2007), ix

[49] Kathleen G. Velsor, The Underground Railroad on Long Island: Friends in Freedom (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2013), 69-74

[50] Mary McQueeney, “Simeon Jocelyn, New Haven Reformer.” Journal of the New Haven Colony Historical Society, 19, no. 3 (1970), 63-67; Anthony Dugdale, J.J. Feuser, and J. Celso de Castro Alves, Yale, Slavery, and Abolition (New Haven, CT.: Amistad Committee, 2001), 16-22, http://www.yaleslavery.org/YSA.pdf

[51] American And Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and Lewis Tappan, The Fugitive slave bill: its history and unconstitutionality: with an account of the seizure and enslavement of James Hamlet, and his subsequent restoration to liberty. (New-York: W. Harned, 1850), Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/96223044/.

[52] Allen, “Commercial Nursery," 130.

[53] Obituary of Samuel B. Parsons, Flushing Times (Flushing, New York), January 5, 1906, as quoted in James Driscoll, “Flushing in the Early Nineteenth Century,” in Angels of Deliverance: The Underground Railroad in Queens, Long Island, and Beyond, ed. Wini Warren (Flushing, New York: Queens Historical Society, 1999), 81

[54] Elijah A. Smith and G. Hayward, Lith., The Village of Flushing, Queens County, L.I.: nine miles east of the city of New York: lat. 40° 45ʹ 1ʺN, lon. 73° 09ʹ 58ʺW. [Flushing?: s.n., ?, 1841] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008620796/.

[55] R. F. O. Conner, M. Dripps, and Korff Brothers. Map of Kings and part of Queens counties, Long Island N.Y. [N. York New York: Published by M. Dripps, N.Y. New York: Engraved & printed by Korff Brothers, 1852] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2013593245/.

[56] Velsor, Underground Railroad on Long Island, 51-55; 99-100.