Minutes of the Council of New Netherland. Quakers in Flushing - Thursday, August 24th 1662

“The magistrates of Rustdorp came here to-day and in form of complaint reported to the Director-General, that the majority of the inhabitants of their village were adherents and followers of that abominable sect, called Quakers, and that a large meeting was held at the house of John Bound [Bowne] in Vlissingen every Sunday. They requested that this might be prevented one way or another. Date as Above.”

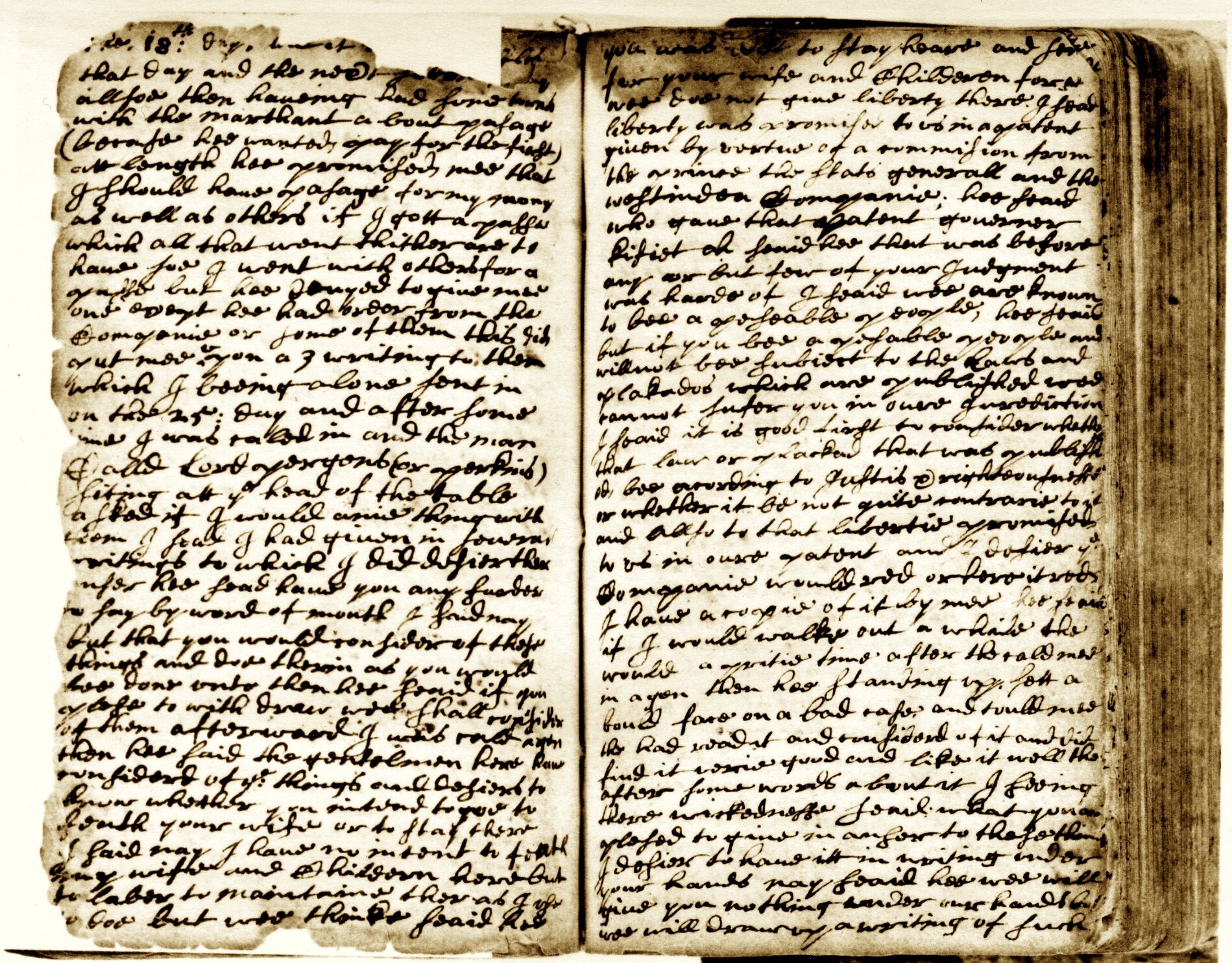

Dutch Colonial Council Minutes, 1638-1665. Volume 10 Part 1, p.199 (New York State Archives Digital Collections) View and download in hi-res

This complaint from the neighboring town of Rustdorp launched Bowne’s ordeal. (Rustdorp was the Dutch name for present-day Jamaica, Queens, while Vlissingen was the Dutch name for Flushing.) Note that the impetus for his arrest came not from the Dutch authorities, but from the magistrates of another English town. Director Stuyvesant was not uniquely intolerant; Quakers, formally known as the Religious Society of Friends, were regarded as nuisances and threats to social order wherever they went. The English authorities, both in England and the Colonies, were actually harsher than the Dutch in their treatment of Friends. The Massachusetts Bay Colony executed four Quakers known as the Boston Martyrs in 1660, while New Netherland never executed any. It’s ironic that in persecuting John Bowne, Stuyvesant was doing something he often drew criticism for not doing- responding to the concerns and petitions of outlying communities on Long Island.

Translation from: Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York Vol. XIV, ed. & trans. B. Fernow (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons, and Company, 1883), 515. Read on Internet Archive