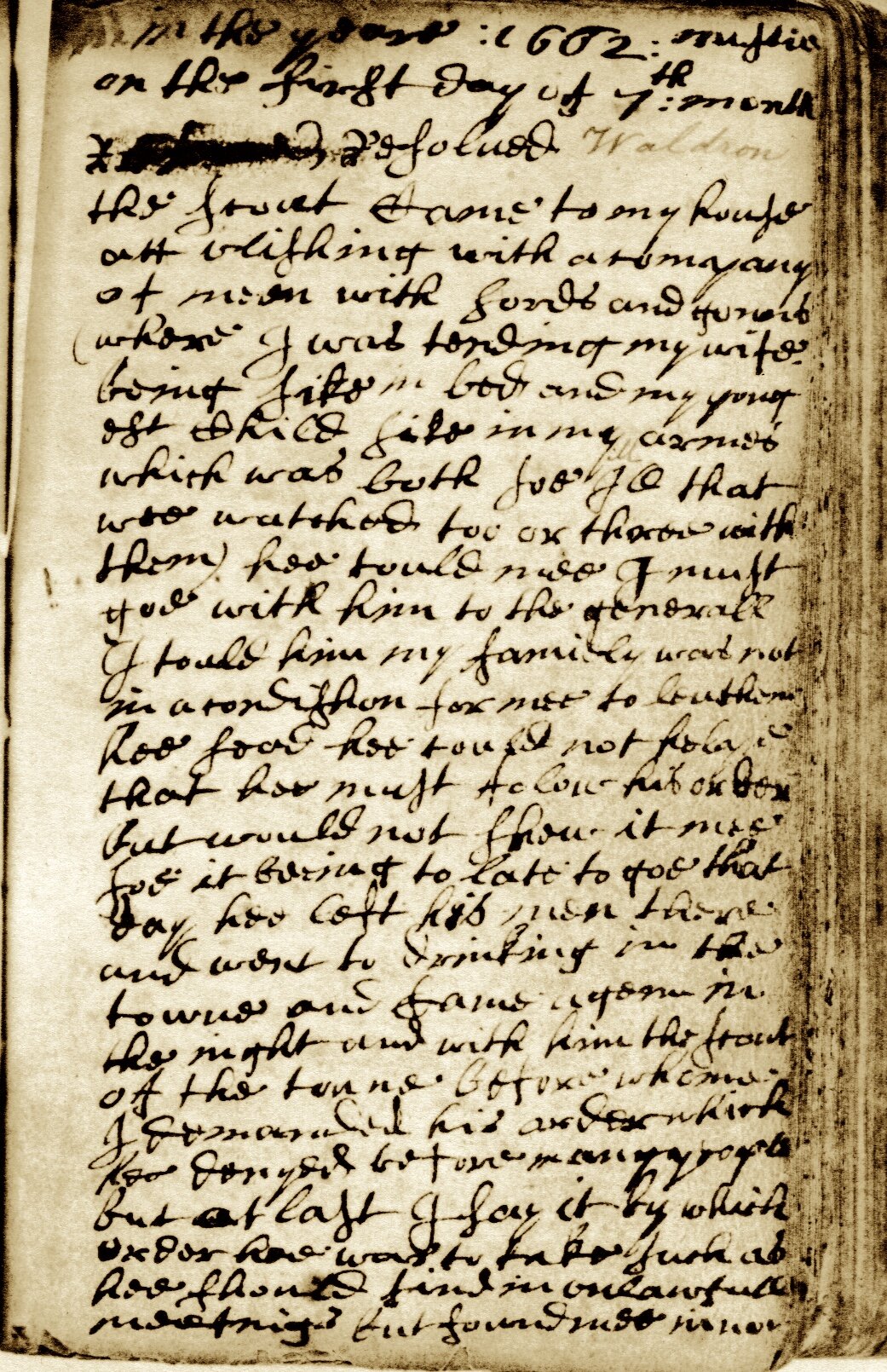

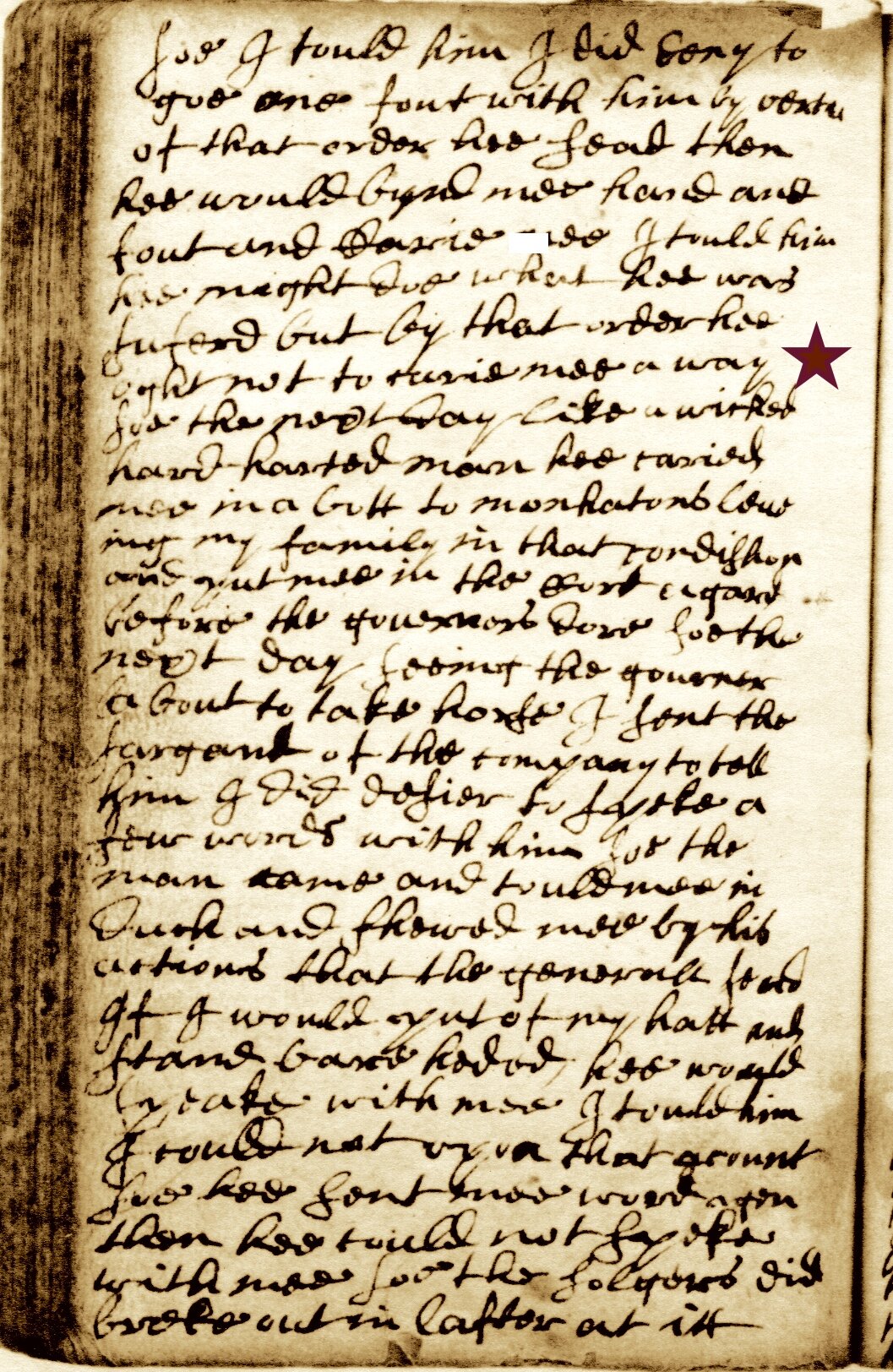

JOURNAL OF JOHN BOWNE: FOLIO 49, RECTO AND VERSO (front and back)

“In the year 1662 on the first day of 7th: month, Resolved the Scout came to my house at Vlishing with a company of men with swords and guns (where I was tending my wife being sick in bed, and my youngest child sick in my arms, which was both so ill that we watched two or three with them.)

(Hover on bottom of images for captions & credits.)

He told me I must go with him to the General. I told him my family was not in a condition for me to leave them. He said he could not help that; he must follow his order, but would not show it me. So it being too late to go that day, he left his men there and went to drinking in the town, and came again in the night, and with him the Scout of the town, before whom I demanded his order, which he denied before many people. But at last I saw it, by which order he was to take such as he should find in unlawful meetings. But he found me in none.

So I told him I did deny to go one foot with him by virtue of that order. He said then he would bind me hand and foot and carry me. I told him he might do what he was suffered, but by that order he ought not to carry me away.” - To be continued on September 12, 1662.

Notes on the Text

“first day of 7th: month” As a devout Quaker, Bowne refers to the months and the days of the week only by number, to avoid the Pagan associations of their names. This gets confusing to a contemporary reader, because Bowne uses the Julian or “Old Style” calendar, in which March is the first month. Furthermore, by the 1600s the old calendar had fallen 10 days behind the modern, or “New Style,” calendar already adopted by the Dutch. Thus Bowne’s “first day of 7th month” means September 1; however, for the Dutch it was already September 11th (and September would have been considered the ninth month, as it is today.) All official documents in New Netherland are dated according to the modern calendar. To avoid confusion in the timeline, this blog will also give the New Style dates for all of Bowne’s entries.

Resolved the Scout: Resolved Waldron -a good Puritan name if ever there was one- was the Schout of New Amsterdam (“Scout” to the English.) Roughly equivalent to a Sheriff, Waldron was the chief law enforcement officer of the province. Although of English parentage, Waldron was a native of Holland and was held in high esteem by Director-General Stuyvesant, who wrote of him: “he conducted himself with so much fidelity and vigilance that he gave to us and the Magistrates great satisfaction.”

Vlishing: Variant of Vlissingen, the Dutch name for Flushing.

“my wife sick in bed”: Hannah Bowne (1637-1678) married John in 1656. She became a Quaker before John, and he credited her with introducing him to their shared faith. Hannah later became a pioneering female Quaker missionary who preached in the Colonies, the British Isles, and on the European continent. At the time of Bowne’s arrest, she was not only ill, but pregnant with their fourth child.

“my youngest child sick in my arms”: Mary “Marie” Bowne, born in January 1661, was about 19 months old.

“go to the General”: New Netherland Director-General Peter Stuyvesant

“too late to go that day”: Before modern transportation, a round trip between Fort Amsterdam in lower Manhattan and Flushing on Long Island would have been difficult or impossible to make in daylight hours.

“the Scout of the town”: Flushing Sheriff, or Town Constable. This position may have been held by John Mastine, who had been appointed by Stuyvesant back in 1658 to replace Tobias Feake, who had been removed from the position for allegedly spearheading the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance. This was an odd choice, for Mastine had himself signed the Remonstrance, a petition that protested the anti-Quaker laws of New Netherland. There is no record of another appointment between 1658 and 1662, so likely he still held the office. If so, his cooperation with Waldron shows that Stuyvesant was right to view him as politically reliable, despite his earlier flirtation with religious liberty. Mastine was an old soldier who had served for many years with the Dutch West India Company and become somewhat assimilated to Dutch society.

“I demanded his order”: Bowne asks to see the warrant for his arrest. This is the order featured in our previous post, issued September 9 (New Style.) The Director and Council of New Netherland authorized Waldron to arrest any person attending illegal religious meetings, and commanded all local authorities to assist him- hence the probably reluctant presence of Mastine. Bowne is not named in the order, but the denunciation of him two weeks earlier has made him a target. (See the August 24, 1662 Complaint by the Magistrates of Rustdorp.) Waldron’s hesitation to show his orders stems from the fact that despite the outstanding complaint against Bowne, he had failed to actually catch his target red-handed in a meeting. Bowne’s keenly legalistic mind hones in on this: “…he was to take such as he found in illegal meetings, but he found me in none,” so “by that order, he ought not to carry me away.”

Introduction to John Bowne’s Journal

With the dramatic scene above, we enter into the Journal of John Bowne, where he documented significant events from 1649 to 1694. By modern genre standards, much of it reads more like a memoir than a journal: a recounting of life’s highlights and milestones, rather than a record of daily happenings. In fact, aside from a few business accounts and the dates of his marriage and children’s birthdays, this is Bowne’s first entry in eleven years. The previous one memorialized his first trip to Flushing, in 1651. Even sequences that unfold from one day to the next with a sense of immediacy are often reconstructed from Bowne’s mental notes whenever the author is next at liberty to write. The above account of Bowne’s arrest was actually written on November 19, when his wife brought his notebook to him in his jail cell in New Amsterdam.

The images of the Journal come from a photostatic reproduction owned by the Bowne House Archives. The original was sold to the New York Historical Society by Bowne’s descendants in the 1920s, and remains in their collection today. The pages of old manuscripts are conventionally called “Folios,” from the Latin word for leaf, with each Folio having a recto (front) and verso (back). We use these terms when labeling the page scans. Finally, 17th century English did not yet have standardized spelling or punctuation, and several letters were formed differently than their modern equivalents (the letter “c” often resembles an “x”, and sometimes looks like a pretzel.) For ease of reading, this blog will modernize all of the above.

REFERENCES

The Journal of John Bowne (photostatic copy courtesy of the New York Historical Society), John Bowne and Early Flushing Research Collection, #2016-2, Box 1, Folder 1. Bowne House Archives.

The Journal of John Bowne (1650-1694), ed. Herbert Ricard, New York: Polyanthos Press, 1975.

Dutch Colonial Records. New York State Archives Digital Collections