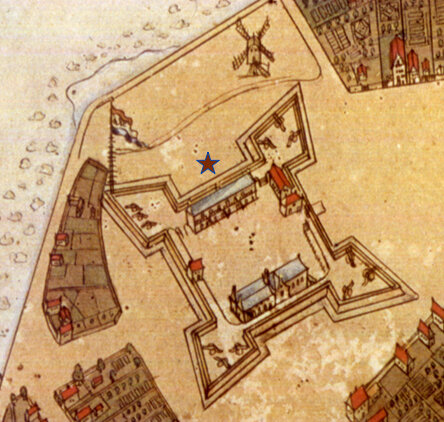

Fort Amsterdam, circa 1661. John Wolcott Adams and I.N. Phelps Stokes, Detail from 1916 redraft of the Castello Plan. (New-York Historical Society)

From September 12 through October 15, 1662, John Bowne was held prisoner at Fort Amsterdam. The above depictions of the Fort where Bowne languished for over a month are taken from the Castello Plan, based on a survey by Jacques Cortelyou taken in 1661. (Note that the top of the map faces West, not North.) The image on the left is a detail from the original map created in the 1660s, while on right we see the same view rendered by John Wolcott Adams and I.N. Phelps Stokes in their 1916 redraft. The long, slate-roofed building, marked with a red star in the map on the left, was the barracks. Across the courtyard stood the Dutch Reformed Church, built of stone, and the red brick Governor’s House, abutting each other in a concrete show of solidarity between Church and State. In actuality, Director Stuyvesant had already moved down the street to his new residence at Whitehall. However, he continued to conduct business at the Fort, where the Council of New Netherland also met and held court, and the building retained its old name.

The small, red-roofed structure on the south-east wall, facing the main gate, may be what Bowne in his Journal termed the “cort-a-garde,” where he was initially confined “just opposite the Governor’s Door.” It resembles a guardhouse or sentry post, where a watchman could simultaneously monitor the entrance to the Fort and mind a prisoner. Alternatively, if Bowne was referring not to the gate but to the literal front door of the Governor’s House, the cort-a-garde must have been part of the barracks. As reported in our last post, on October 5 Bowne was carted away to what he calls a “dungeon” after refusing to pay the judgment against him. The Castello plan does not show the location of this dungeon. However, the basement of the barracks seems the likeliest candidate.

“1653-1664, Amsterdam in New Netherland, the City of the Dutch West India Company.” Townsend MacCoun, 1909.

The map above, by American cartographer and historian Townsend MacCoun, depicts Manhattan between 1653 and 1664. While not so pleasing to the eye as the Castello Plan, this map helpfully labels many streets, buildings, and other features of interest, including “White Hall,” Stuyvesant’s new mansion, the City Hall (Stadt Huys), and even the nearby public stocks on the waterfront.

Today, the site of Fort Amsterdam is home to the Museum of the American Indian, the Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York, and the National Archives for New York, resident inside the former Alexander Hamilton Customs House. The landmarked Beaux-Arts building at One Bowling Green was designed by the architect Gilbert Cass and constructed by 1907. The downside of this grand monument to the old Fort is that it effectively rules out any archaeological investigations of the layers beneath.

Photo: Looking Southeast towards the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House at dusk. Jim Henderson, 2008. (Wikimedia)

LINKS

Print of the original Castello Plan from the NYPL Digital Collections: Phelps Stokes Collection of American Historical Prints. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-7c0b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

(The original manuscript is in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana of Florence, Italy.)

1916 redraft of the Castello Plan by John Wolcott Adams (1874–1925) and I.N. Phelps Stokes (1867–1944) from the New York Historical Society Library, Maps Collection: https://www.nyhistory.org/web/crossroads/gallery/all/castello_plan_redraft.html