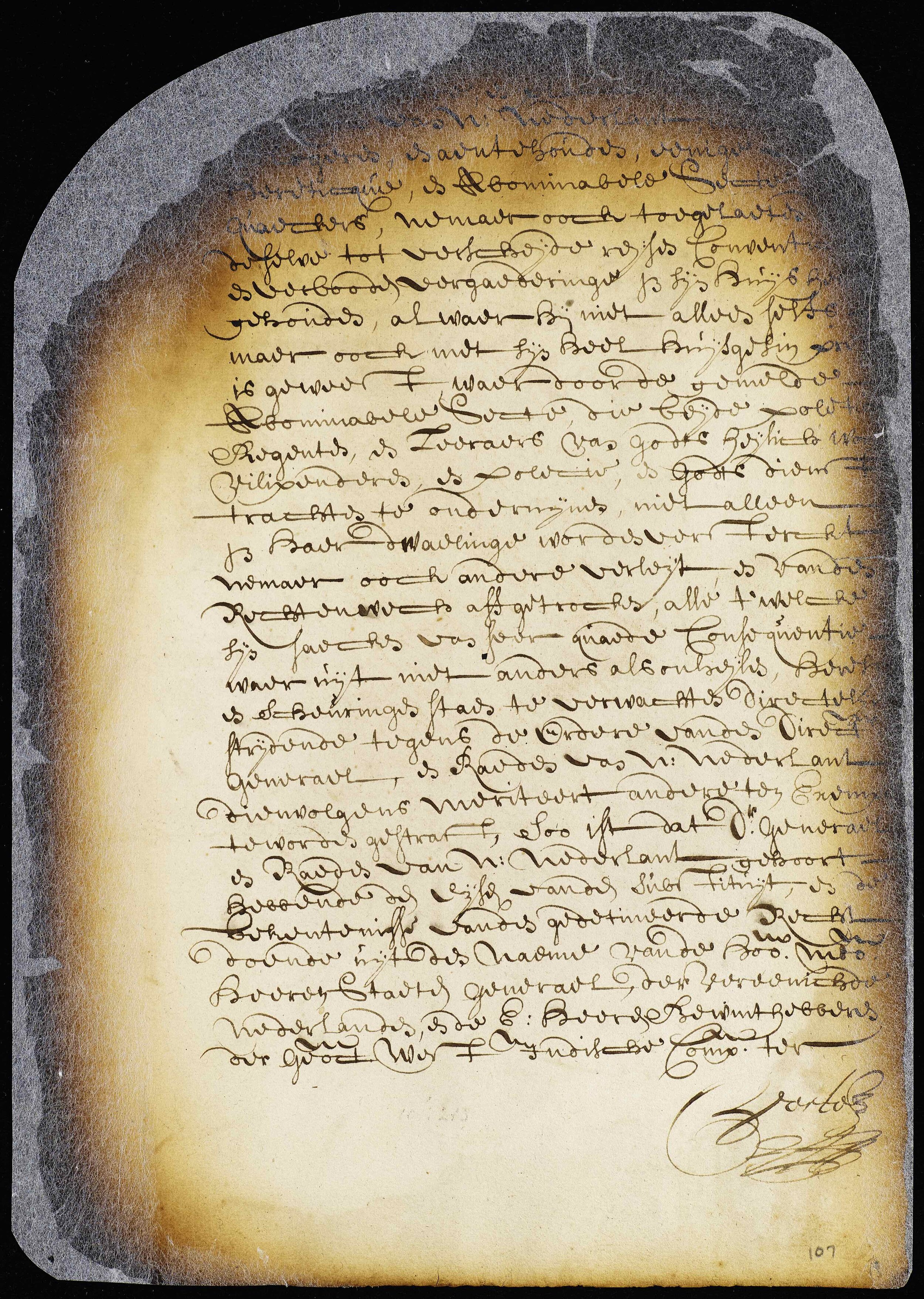

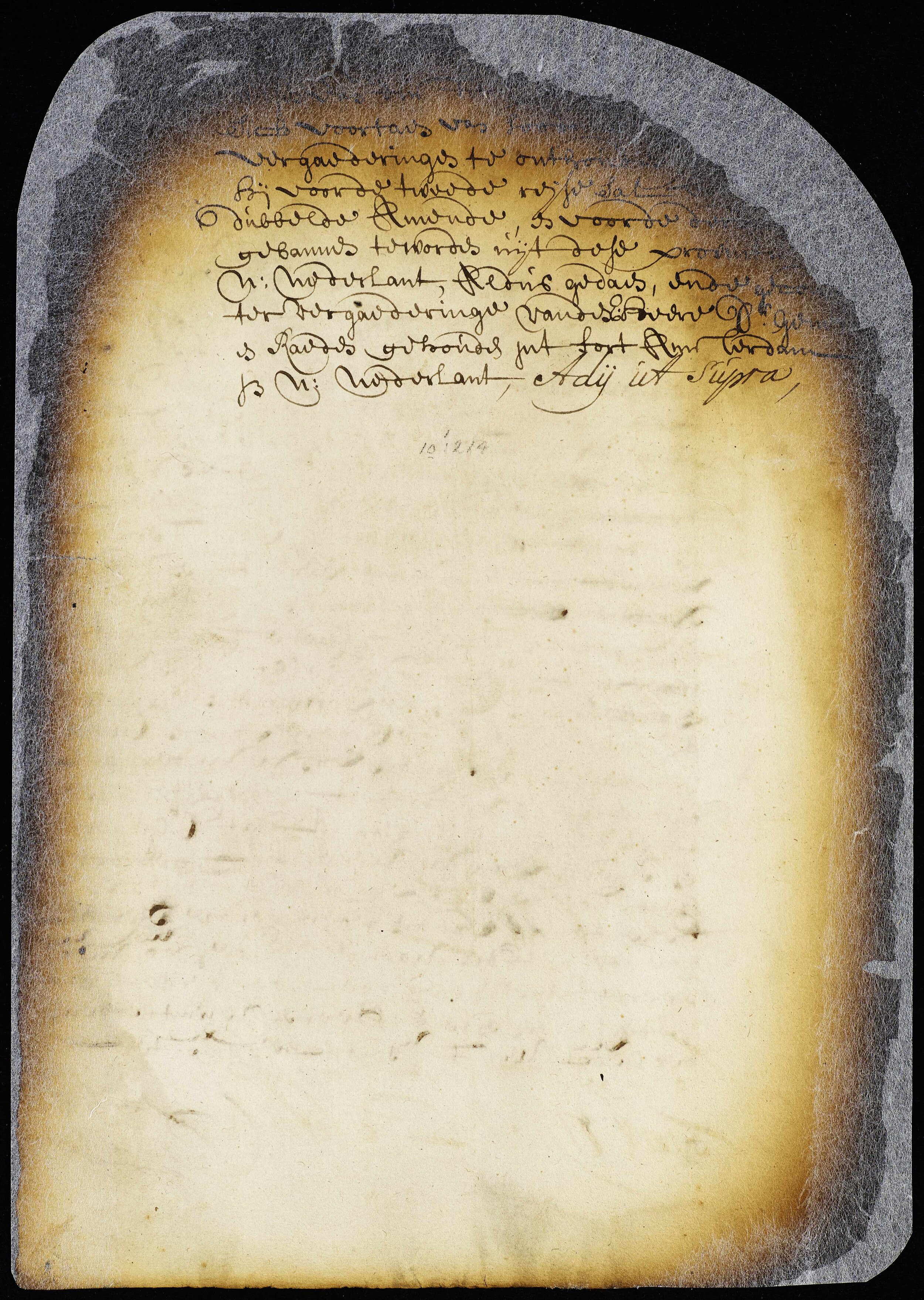

Criminal Complaint Against John Tilton, a Prisoner, for attending meetings of Quakers

To the Great and Respectful Director-General and Council of New Netherland,

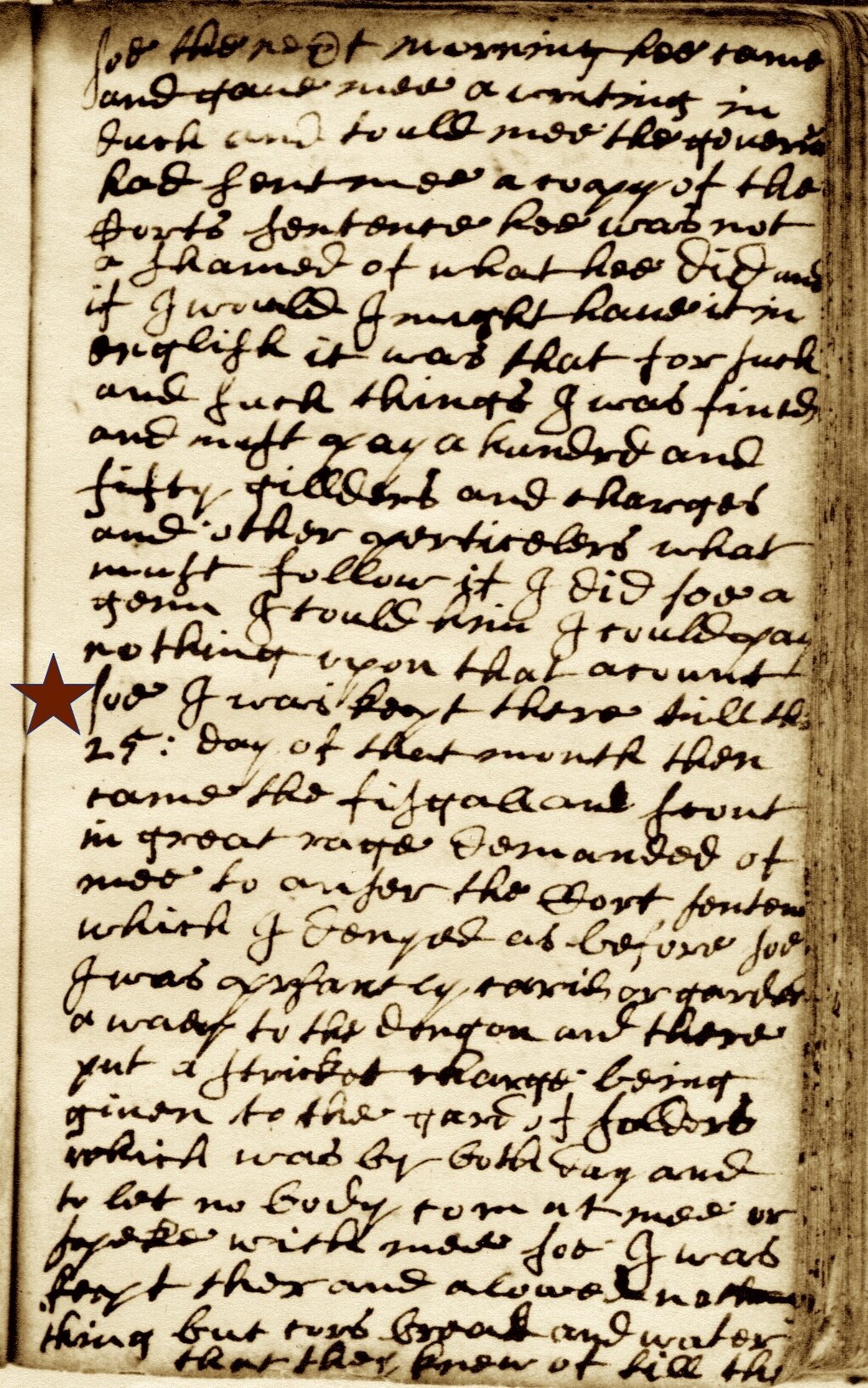

Showeth, reverently, Schout Nicholas de Sille, how that John Tilton, now a prisoner here, continues to frequent all the conventicles of the Quakers, and even permits the Quakers to quake at his house, not remembering the great favor and merciful sentence given by your Honors on the 10th January 1658, nor the sentence pronounced on the 20th January, 1661, by which he was commanded to depart out of this province, on the penalty of corporal punishment, but that he treats it with contempt, and proceeds in his malice, protects that heretical sect, contrary to the orders and placards published on this subject, for which he, as an example for others (being that the Quakers are such forgetting men), ought to be punished; so is it, that the Attorney-General, nominee officin, concludes that John Tilton aforesaid ought to be condemned to a fine of £100 Flanders, and further, to remain in prison until the aforesaid fine shall have been paid, with the costs and fees of justice.

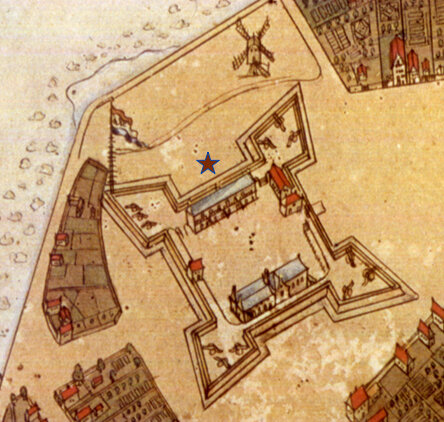

Done in Fort Amsterdam, 19th September, 1662.

Your N, G, and R servant, Nicholas de Sille

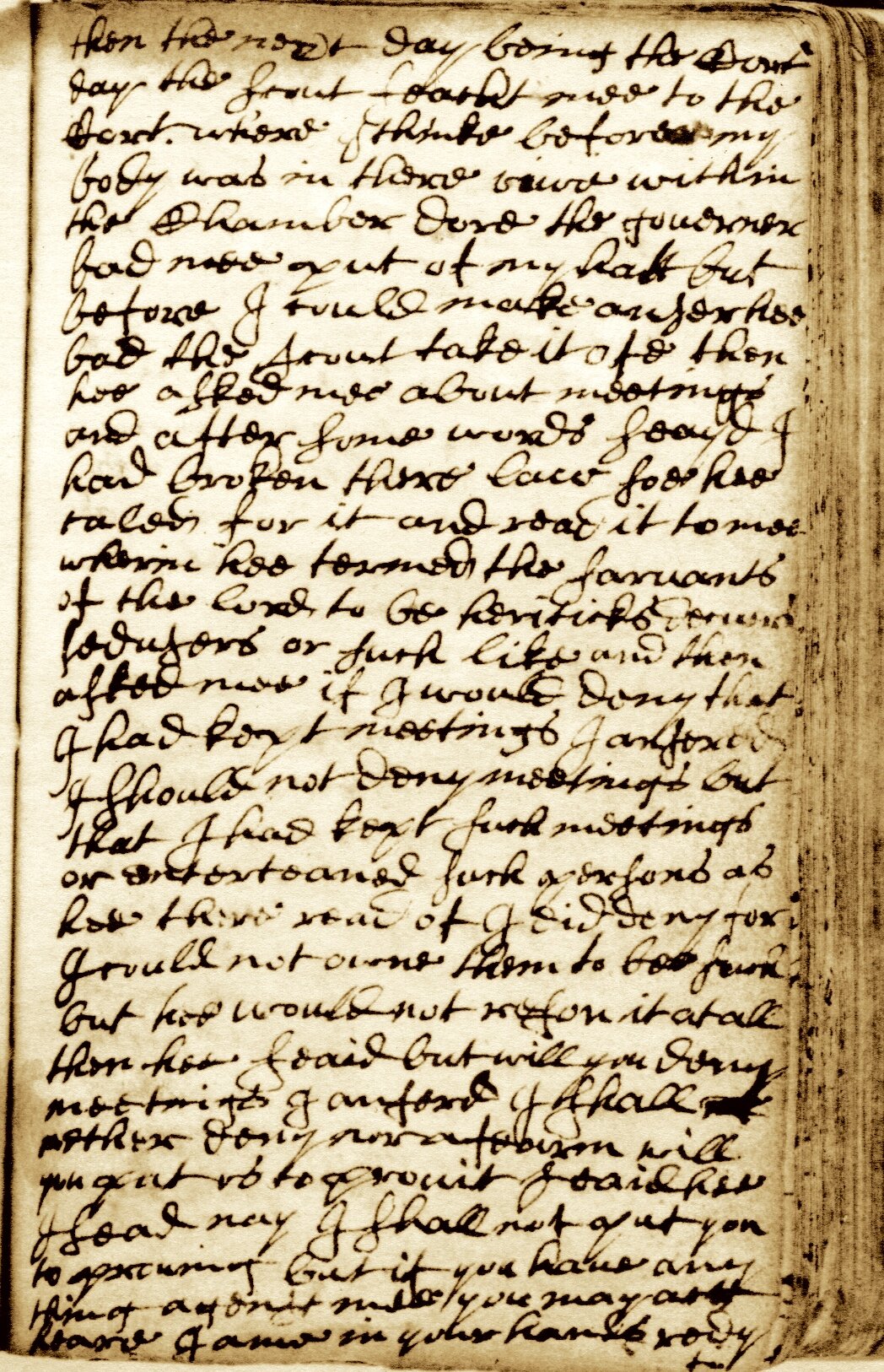

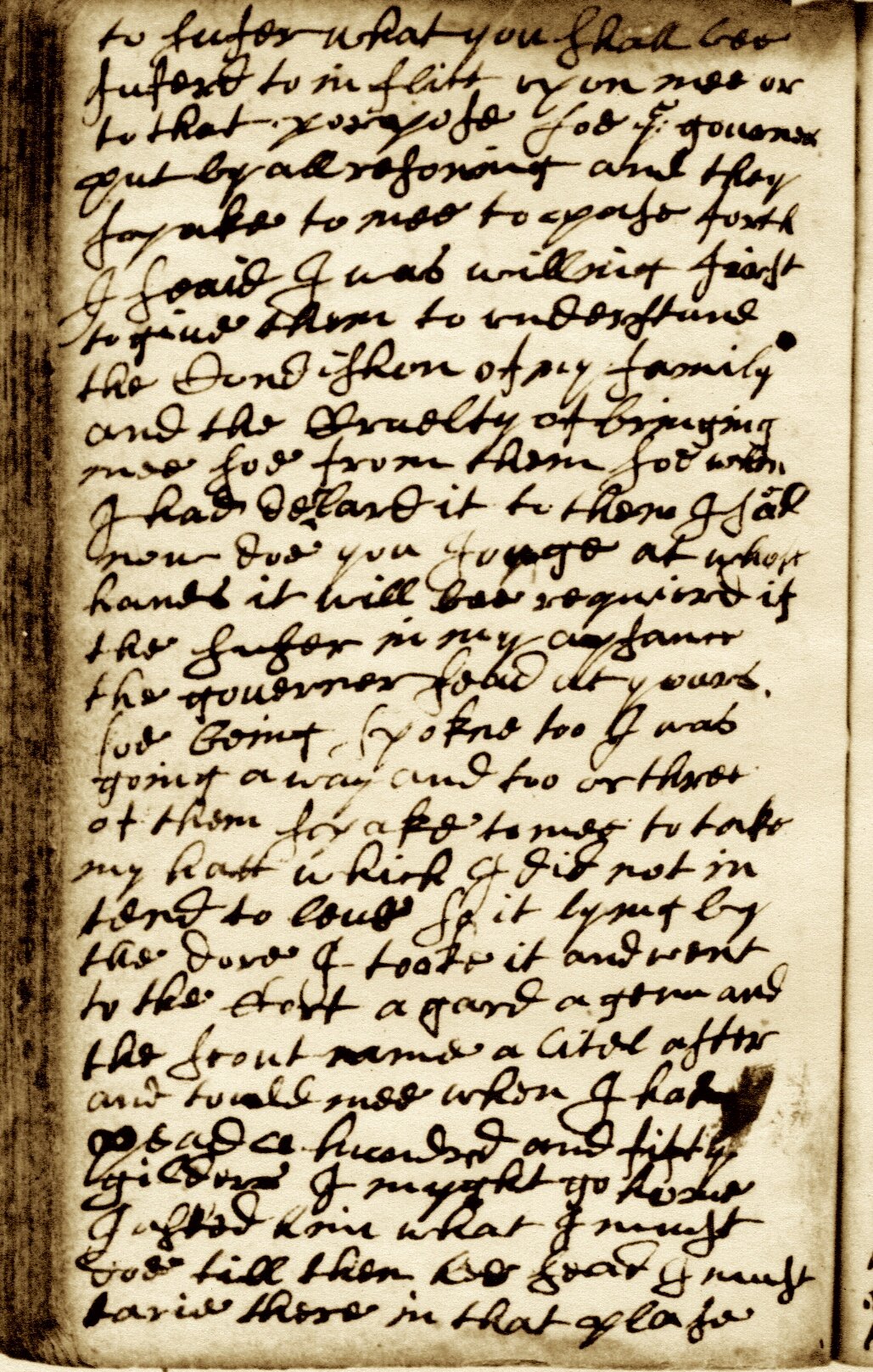

Complaint Against Mary Tilton, a Prisoner, for attending meetings of “that abominable sect called Quakers.”

To the Noble, Grand, Respectful Director-General and Council of New Netherland,

Whereas Mary Tilton, wife of John Tilton, now a prisoner here, has dared not only to assist at all the meetings of that abominable sect who are named Quakers, but even has presumed to provide them with lodgings and victuals, and has endeavored to go from house to house, and from one place to the other, and to lure the people, yea, even young girls, to join the Quakers, and already with several succeeded, encouraging and supporting them; so it is highly necessary now, to prevent all calamities, schisms, and confusion, as far as it is possible, that there be a stop put to it, and that such persons be punished, as an example for others, on which the Attorney-General concludes, ex officio, that the aforesaid Mary Tilton shall be condemned in £100 Flanders, and further, to be banished out of the province of New Netherland, and to remain in prison until the sentence shall be satisfied, with the costs and fees of justice.

Done in Fort Amsterdam, in New Netherland, on the 19th September, 1662.

Your N., G., and R. servant, Nicholas de Sille

Notes on the Text

JOHN TILTON:

Nicholas de Sille: the Provincial Schout-Fiscal, similar to Attorney-General. Referred to by Bowne as “the Fiscal.”

conventicles: forbidden religious gatherings held in private homes or other hidden places

“permits the Quakers to quake at his house”: Quaker was originally a derogatory label applied to Friends, whose bodies would quiver and quake with the fear of God when they worshiped or testified.

“the merciful sentence [of] 10th January 1658”: John Tilton had previously been charged with harboring Quakers, in the aftermath of the Flushing Remonstrance. As a first-time offender, he was just charged twelve pounds Flemish (one-half of the usual fine for attending conventicles.)

“the sentence pronounced on the 20th January, 1661”: Tilton had been exiled out of the province on pain of a severe whipping after resuming his Quaker activities in 1661, but clearly he slipped through the cracks and never actually left.

“contrary to the orders and placards”: The text of the Quaker ban has not survived; we know about it from references such as these in court proceedings.

£100 Flanders: Four times the fine assessed to first-time offender John Bowne. Roughly equivalent to $36,000 in contemporary money.

“Your N., G., & R. servant”: Noble, Grand, and Respectful

MARY TILTON

“schisms, calamities, and confusion”: the devout Dutch Reformed officials of New Netherland feared that other sects would lure their citizens away from the “true Church” with false doctrines, potentially jeopardizing their souls. They also believed that God would punish the colony with epidemics, Indian attacks, or other disasters if the populace sinned.

“to be banished out of the province”: Mary’s recommended punishment of £100 and banishment is more severe than John’s, although she has not been sentenced before. One genealogy written by a descendant of Nicholas de Sille notes the Schout-Fiscal “was especially severe on female offenders,” citing a case in which he deported a housewife to Holland stand trial for fighting with another woman, also recommending a prison term for hoisting her petticoat too high in respectable company. De Sille’s comments about “young girls” being enticed to join the Quakers is revealing in this light.

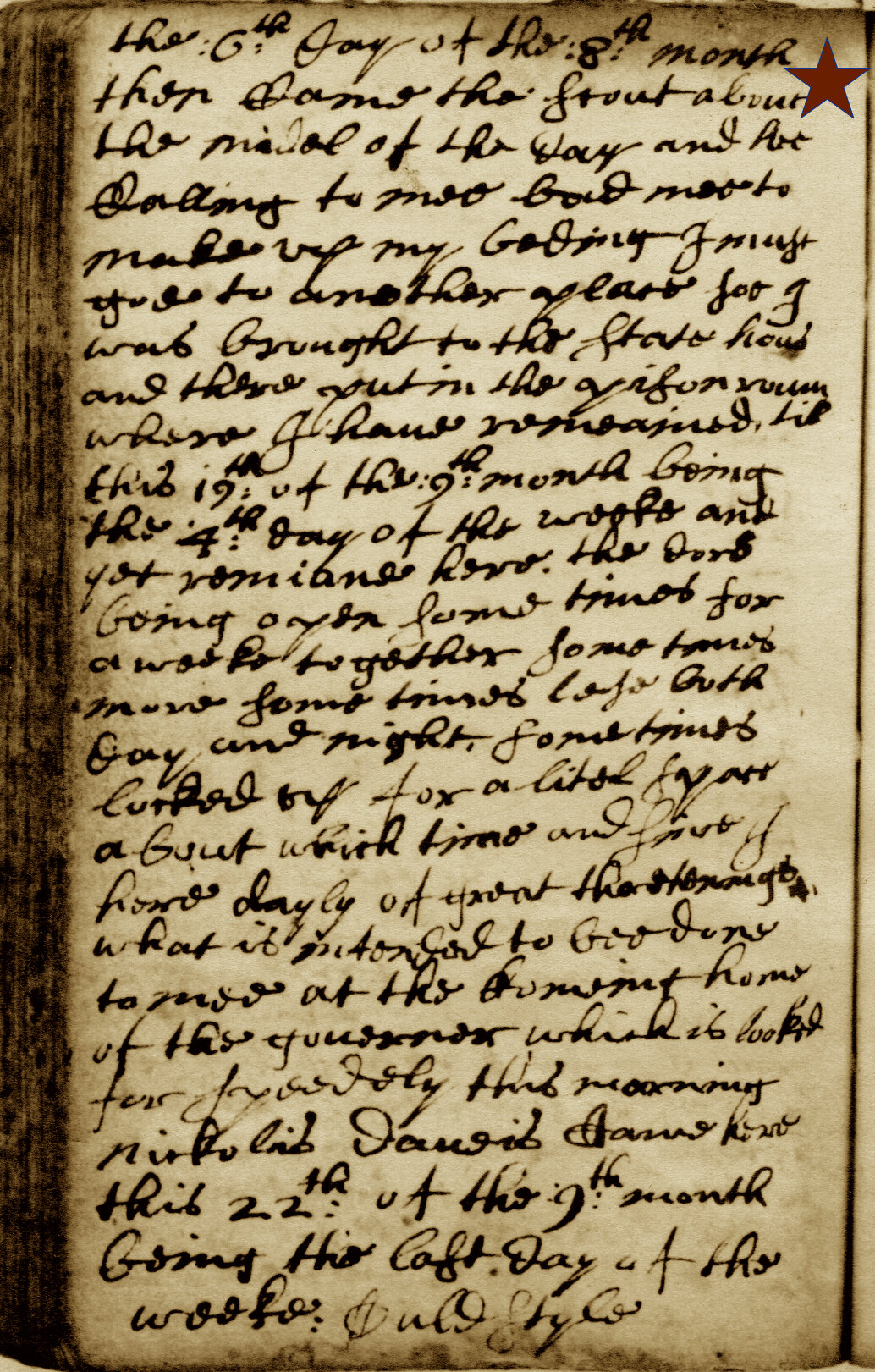

Coming September 20: Bowne must pay to read his own sentence.

REFERENCES

New York State Archives Digital Collections. Dutch Colonial Records. Minutes of the Council of New Netherland, 1638-1664. http://digitalcollections.archives.nysed.gov/index.php/Detail/objects/55296

Religious Society of Friends, “The Early Settlement and Persecution of Friends in America.” Friends’ Intelligencer I, no. 5 (Fifth Month, 15th, 1838): 54-59, 83-87, 102-106. Google Books

Reference to Nicholas de Sille found in: Kip, Frederick Ellsworth, The Kip Family in America, (Boston: Hudson Printing Co., 1928) 32-3. Internet Archive